Reading books is an activity that becomes part of students’ lives from the early days of elementary school (Piasta et al., 2018). Reading fiction texts is closely linked to improving reading comprehension and is an opportunity to engage readers in different types of adventures (Westbrook et al., 2019). Additionally, reading fiction texts may profoundly impact how students feel and behave in their daily lives (Mak & Fancourt, 2020). In this context, current studies have emphasized an important aspect concerning the effect of reading fiction texts on the reader’s level of empathy (Mumper & Gerrig, 2017). Studies suggest that people who frequently read fiction texts become more empathic because fiction simulates social experiences, which is an opportunity for people to practice and improve interpersonal skills (McCreary & Marchant, 2017; Mumper & Gerrig, 2017).

Fiction texts are those that tell a story, stimulating the readers’ imagination (Oatley, 2016). The term fiction is generally used to distinguish imaginary events from the real world. Hence, literary fiction belongs more to the realm of possibilities than to real life (Mak & Fancourt, 2020). From this perceptive, works of fiction are not intended to provide information or detailed knowledge of the world; instead, fiction stimulates the readers’ imagination of different times, places, and even cultures (Oatley, 2016). Therefore, fiction readers might understand others better partially because they engage in these stories by making emotional inferences about characters and complex circumstances, which is possibly not easily found in their daily lives (Oatley, 2016).

The concept of empathy may be understood as a person being psychologically attuned to someone else’s feelings and perspectives (Decety & Lamm, 2006; Szalavitz & Perry, 2010). This definition is related to a broadly accepted observation: empathic skills are multidimensional (Davis, 1980, 1983) - composed of different emotional components, confirmed by a willingness to become concerned and feel compassion for others (Israelashvili et al., 2020); and cognitive components, evidenced by the possibility of conceiving points of view different from one’s own (Decety & Lamm, 2006).

Empathy can be divided into two categories: affective and cognitive (Davis, 1983). Affective empathy is the ability to share/understand someone else’s feelings without experiencing any direct emotional stimulus, whereas cognitive empathy is the ability to recognize and understand someone else’s mental state (Davis, 1983). Additionally, empathy is associated with a broad range of intrapersonal and interpersonal skills (Konrath & Grynberg, 2013) and is positively related to satisfaction with life, emotional intelligence, and self-esteem (Eisenberg et al., 2006).

As empathy is understood as a competence or attitude toward other people’s feelings (Israelashvili et al., 2020), research in the education and psychology fields have shown that interventions may increase empathic competence among students from different educational levels (Guarisco & Freeman, 2015; Riquelme & Montero, 2013). The reason is that readers of fiction texts tend to have better empathic skills than those who do not read this textual genre (Mar et al., 2011). In this sense, reading this type of genre has shown an important relationship with the development of empathy (Mar & Oatley, 2008) because when a narrative engages a reader, they start to understand different points of view and may develop both affection and cognition (Israelashvili et al., 2020).

According to Mar and Oatley (2008), when reading a fiction text, individuals simulate - that is, feel and experience - thoughts congruent with those depicted by the story’s characters. Readers may also learn about the complex social world, abstracting meaning, establishing inferences, and making predictions about the development of the narrative and the interpersonal relationships presented in the story. As reading makes it possible to indirectly experience the same subtleties of social interaction and difficulties experienced by the characters of a fiction story, Mar and Oatley (2008) suggest that readers’ empathy develops and improves in the process.

Therefore, reading fiction stories may be associated with developing empathy among children, suggesting an important connection between empathy with fictional characters and the ability to manifest empathy with people in real life (Aram & Aviram, 2009). In this context, Mar and Oatley (2008) note that the involvement of children and adults with the fictional world overflows into the real world. In other words, the readers’ experience is transferred to real life, and readers become more empathic people.

Often, it is only possible to understand a story by putting oneself in the protagonist’s place, understanding the character’s beliefs and difficulties, which happens when readers exercise cognitive empathy (Lodge, 2002). According to Lodge (2002), a characteristic of literary fiction is that it can provide detailed descriptions of each moment of a protagonist’s thoughts and feelings, providing a rich opportunity for readers to experience cognitive empathy. Affective empathy has also been established as an essential component for understanding and enjoying reading (Hogan, 2010). Hogan (2010) argues that literary representations of emotions can be more authentic than the real life’s, and, therefore, they have the power to improve one’s affective empathic responses.

Empathy has been a topic of great interest among psychologists, educators, and neuroscientists and is related to various topics and situations that have regularly emerged from new studies. Therefore, given the previous discussion, this study’s objectives include: 1. identifying the main studies addressing the relationship between reading fiction texts and empathy among children; 2. verifying how the two primary dimensions of empathy (i.e., affective and cognitive) are addressed in studies investigating the practice of reading fiction texts; and, finally, 3. examining the factors associated with elementary school students reading fiction texts that collaborate to the development of empathy.

Method

Study design

This integrative literature review is intended to map the topic of reading and empathy and develop an integrated and critical debate, unveiling scientific evidence in the field and identifying potential gaps. In this sense, this review is based on the procedures proposed by Mendes et al. (2008), namely: 1. identifying a theme; 2. establishing inclusion/exclusion criteria; 3. categorizing studies; 4. assessing the studies selected; 5. interpreting results; and 6. synthesizing knowledge. We independently identified and selected the studies.

Databases and descriptors

As previously mentioned, this study focuses on studies addressing the reading of fiction texts and its relationship with the development of empathy. The indexed papers were systematically searched in the following databases: Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO), Education Resources Information Center (ERIC), and PsycInfo - a database in the field of psychology developed by the American Psychological Association (APA). These databases were chosen because they cover most Brazilian and international studies in the psychology and education fields. The following descriptors were used: “Empathy”, “Reading”, “Reading Comprehension”, and “Fictional Reading” and their equivalent in Portuguese: empatia, leitura, compreensão textual, and leitura de ficção. These descriptors should be found in at least one of the following items: title, keywords, subject, or abstract. Additionally, the descriptors were combined using the Boolean operator AND.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria: 1. indexed papers addressing the topic, published in Portuguese, English, or Spanish between 2009 and 2020 - this timeframe was chosen because a study published in 2009 is repeatedly cited by other papers and presents an important contribution to the debate on empathy considering children’s reading practices (Aram & Aviram, 2009); 2. empirical studies addressing the relationship between reading and empathy.

Exclusion criteria: 1. doctoral dissertations, master’s theses, and undergraduate monographs; 2. studies indexed and published before 2009; 3. studies addressing students other than elementary school students, adults, or individuals older than the age group considered in this research, such as individuals attending youth and adult education programs and/or college students; 4. studies that did not directly address the topic or only superficially mentioned the relationship between empathy and reading; 5. theoretical or bibliographic reviews.

Procedures

Data collection

The papers were selected in June 2020. First, the abstracts identified by their descriptors and according to Boolean searches were read in detail. Then, duplicated papers and papers that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. The descriptors and their combinations were used in SciELO, ERIC, and PsycInfo databases accessed via BVS-Psi. Finally, the papers identified were read and analyzed according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria established for this review.

Data analysis

The papers selected were organized in an Excel spreadsheet for further analysis according to the following items: title, year of publication, authors, journal, study design, sample, theoretical framework, instruments, objectives, results, and main findings. Thematic categories were created based on this classification to present a profile of the papers addressing reading practices and empathy among elementary school students. Therefore, data were analyzed based on these categories, exploring the studies’ results and gaps concerning the topic under analysis. Thus, the results are presented according to the following thematic categories: 1. effects of reading on empathy among children and adolescents; 2. how reading impacts the cognitive and affective components of empathy; 3. factors associated with the reading of fiction texts that collaborate to the development of empathy among elementary school students; and 4. identifying the perspectives of the relationship between reading and empathy.

Results

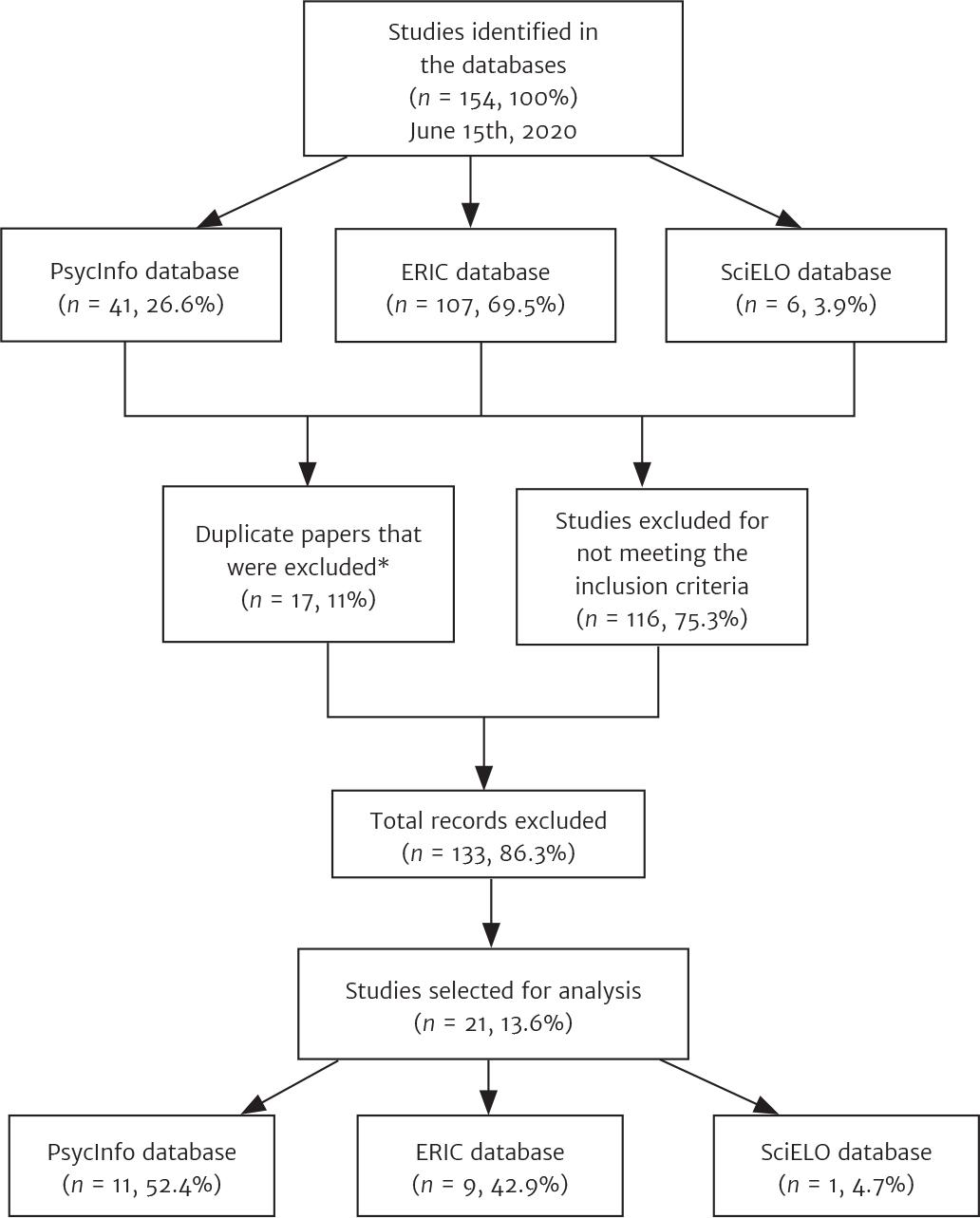

The initial searches led to the following results in terms of the number of papers found: SciELO (n = 6), ERIC (n = 107), and PsycInfo (n = 41), totaling 154 records. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria and excluding those documents that appeared more than once, 21 papers remained. The excluded papers were theoretical studies addressing concepts of empathy and how it relates to reading, or describing how emotions, especially empathy, are associated with reading, or even empirical studies addressing college students or adults. Hence, the final corpus of analysis is composed of the full texts of 21 papers, as shown in Figure 1.

Note. * 17 duplicated studies, 16 identified in the PsycInfo and ERIC databases; and one was identified in PsycInfo and SciELO.

Figure 1 Flowchart of the systematic review process based on the PRISMA protocol

After reading, analyzing, and categorizing the studies, a profile was organized considering the following characteristics: study design, sample, and theoretical perspectives. The results are presented in Table 1.

Table 1 Classification and frequency of papers listed in terms of study design, sample, and theoretical perspective (n = 21)

| Classes | Characteristics, absolute frequency, and percentages |

Examples in the sample |

|---|---|---|

| Study design | Intervention study (n = 8, 38.1%) Case study (n = 7, 33.3%) Correlational study (n = 6, 28.6%) |

Riquelme and Montero (2013)

Lysaker and Sedberry (2015) Lonigro et al. (2014) |

| Study sample | Students (n = 16, 76.2%) Teachers and students (n = 4, 19%) Parents and students (n = 1, 4.8%) |

Venegas (2019)

Bostic (2014) Deschamps et al. (2014) |

| Theoretical perspective | Education and psychology theorists propose that reading develops morals and empathy (n = 18, 85.7%). |

Brett (2016) |

| Socioemotional skills, focus on empathy as part of the schools’ curricula (n = 3, 143%). | Schonert-Reichl et al. (2015) |

Regarding the design of studies addressing reading and empathy, most were intervention studies (n = 8; 38.1%). In the study presented as an example, Riquelme and Montero (2013) planned and implemented an (quasi-experimental) intervention to promote emotional competence among children ranging from six to eight years old through the reading of children’s literature. In addition to intervention studies, case studies (n = 7; 33.3%) and correlational studies (n = 6; 28.6%) were also found. These studies report that the ability to read literary texts influences and develops empathy among students; however, few studies investigate an inverse relationship, that is, whether empathy can predict and/or develop students’ reading comprehension.

The samples addressed by the studies selected for this review primarily comprise elementary school students (n = 16; 76.2%); though, some studies included teachers’ perceptions regarding the investigations conducted among the students (n = 4; 19%). Only one study collected the perception of the students’ parents/legal guardians (Deschamps et al., 2014). Even though all the studies were conducted in public schools, one study also included private schools (Jensen et al., 2011).

In recent years, researchers from the psychology and language fields have noted a significant association between fictional narratives and emotional experiences (Aram & Aviram, 2009; Brett, 2016; Karniol, 2012). Among possible emotional experiences, empathy - with its cognitive and affective components - stands out as one of the skills most frequently developed by reading (McTigue et al., 2015). The reason is that a fictional book can incite feelings and identifications from sorrow, given the difficulties the characters experience, to smiles, caused by the characters overcoming previously insurmountable challenges (Guarisco & Freeman, 2015). Thus, as this review shows, many theorists propose (n = 18; 85.7%) that literary fiction encourages, develops and strengthens one’s empathic skills (Hibbin, 2016; Lysaker & Sedberry, 2015). Additionally, the fact that the development of socioemotional skills was recently added to school curricula reinforces the importance of promoting empathy through literature (Schonert-Reichl et al., 2015), which is reported by some studies addressed here (n = 3; 14.3%).

Additionally, the methods, procedures, and instruments used show that the interventions were organized with pretests and reading tests (McTigue et al., 2015) and empathy scales (Schonert-Reichl et al., 2015) applied to students, followed by interventions (Guarisco & Freeman, 2015; McTigue et al., 2015), and, finally, post-tests repeating the set of tests applied in the initial investigation to measure differences in reading tests and empathy for the control and experimental groups (Riquelme & Montero, 2013). The case studies primarily involved observations (Venegas, 2019) and interviews (Lysaker & Sedberry, 2015) based on fiction texts, including empathy (Parsons, 2013) and reading measures (Newstreet et al., 2018). Most correlational cross-sectional studies verified whether the reading of narrative texts predicted levels of empathy among students (Chisholm et al., 2017; Jensen et al., 2011).

As previously mentioned, more than 90% of the studies, within their different specificities, investigated how reading influenced the development of empathy (Aram & Aviram, 2009; Chisholm et al., 2017; McTigue et al., 2015; Merga, 2017). In addition, there were studies analyzing whether the students’ levels of empathy influenced their performance in comprehension of literary texts and other academic competencies (Schonert-Reichl et al., 2015).

In the last decades, researchers have argued that reading narrative texts provide demonstrable social benefits, especially those concerning the development of empathy (Mar & Oatley, 2008). From this perspective, most studies highlight that literary reading may lead to the development of moral and social skills, but mainly empathy (n = 18; 85.7%). It is worth noting that more recent studies considered the theoretical perspective of socio-emotional learning essential to the school curriculum (Venegas, 2019), focusing on empathy as a skill to be developed by students taking part in studies (n = 3; 14.3%).

Discussion

Studies show that by engaging with the reading of literary texts, students may improve their empathy skills at the various levels of elementary schools (Karniol, 2012; Nikolajeva, 2012; Parsons, 2013). This statement is supported by various empirical pieces of evidence (Chisholm et al., 2017; Merga, 2017; Newstreet et al., 2018). In turn, the students’ level of empathy may be related to their reading comprehension skills (Lonigro et al., 2014). With this in mind and considering the profile of the studies selected in this review, we shall discuss the main findings and what seems to be controversial in these studies.

The effects of reading on the empathy level of children and adolescents

The way fictional narratives present characters, events, and the plot transport the students/readers to a fictional world. For this reason, it is believed that a story may change them (Aram & Aviram, 2009; Jensen et al., 2011). It occurs because fiction simulates real-world problems, which has consequences for readers (Guarisco & Freeman, 2015; Fjällström & Kokkola, 2015). Furthermore, reading fictional books develops both the affective and emotional components of empathy (McTigue et al., 2015) - something non-fiction texts, such as newspapers and magazines, for instance, do not seem to promote (McTigue et al., 2015). Hence, the journey initiated with reading narrative texts transforms students, as it incites various processes, including emotional involvement with the story and identification with characters (Hibbin, 2016; Lysaker & Sedberry, 2015; McTigue et al., 2015).

Jensen et al. (2011) found that reading for pleasure leads students to seek fictional books more frequently and influences their emotional engagement with reading. When readers transport themselves to a literary text, a mechanism of emotional identification with characters is activated, increasing the involvement of (fourthand fifth-grade) students with the narrative and encouraging the understanding from someone else’s perspective, which results in the development of cognitive empathy. In line with this, Chisholm et al. (2017) implemented an intervention so that students developed empathy through reading fiction texts. Their results revealed an improved ability to establish inferences related to emotions, showing that reading promoted both reading comprehension and affective and cognitive empathy among the students participating in the intervention compared to the control group.

Most of the studies selected for this review were based on the hypothesis that reading fiction texts promotes empathy (Merga, 2017; Parsons, 2013). However, a few studies investigated the readers’ level of empathy and how it influences reading (Bostic, 2014; Lonigro et al., 2014). Bostic (2014), for instance, analyzed whether empathy demonstrated by elementary school teachers contributed to motivating students to read and improve their reading performance; however, the results did not suggest a connection between teachers’ empathy and students’ performance in reading tests. Lonigro et al. (2014), in turn, directly focused on fourthand fifth-grade students and attempted to understand how one’s empathy level favored engagement with reading activities. The results showed that more empathic students were better at interpreting literary texts because they were more competent in recognizing the characters’ emotions and feelings.

The results of many of the studies of this review suggest that reading narrative texts plays a socializing role among students, especially favoring the development of empathy - in its affective and cognitive components (Guarisco & Freeman, 2015; Venegas, 2019). Also, implementing reading while promoting empathy as part of schools’ curricula of elementary school improves school climate (Brett, 2016; Schonert-Reichl et al., 2015) and the performance of early grade students being literate (Karniol, 2012; Merga, 2017). Another factor that deserves to be highlighted is that students become more engaged with the topics discussed in class - especially pre-adolescents and adolescents, considering that cognitive empathy is more consistently found among adolescents than among children -, with their peers and teachers, because they start to understand others’ perspectives, detaching from their own points of view (Bostic, 2014; Newstreet et al., 2018).

How does reading impact empathy’s cognitive and affective components?

This study defines empathy according to Davis (1980, 1983): cognitive and intellectual capacity to recognize other people’s emotions and provide an emotional response. In recent years, the reading of narrative texts is believed to promote affection and cognition among children (Nikolajeva, 2012), adolescents (Fjällström & Kokkola, 2015), and adults (Mar & Oatley, 2008). However, only studies addressing children and adolescents enrolled in elementary schools were included in this review. In this sense, we sought to analyze potential differences in the effects promoted by reading on the development of the cognitive and affective components of empathy.

Studies in the field tend to investigate the cognitive and affective components simultaneously (Chisholm et al., 2017; Riquelme & Montero, 2013). However, some studies show that children attending the first, second, or third grades, or initiating the literacy process, present more significant development of the affective component (Karniol, 2012; Merga, 2017; Nikolajeva, 2012) than the cognitive one. The pedagogical work with fiction texts, in turn, has shown a significant development of the cognitive component among students from the fourth grade onwards (Jensen et al., 2011; Newstreet et al., 2018; Parsons, 2013). Reading leads students to infer the characters’ thoughts and feelings (McTigue et al., 2015). The fact that students need to understand the narrator and the primary and secondary characters’ different points of view promotes the development of cognitive empathy (Guarisco & Freeman, 2015; Lysaker & Sedberry, 2015).

The development of cognitive empathy, promoted by reading literary texts, has been associated with creative writing, decreased anxiety (Betzalel & Shechtman, 2010; Hibbin, 2016), a higher level of understanding of social justice, and decreased prejudice and discriminant behavior toward different opinions (Lysaker & Sedberry, 2015; Newstreet et al., 2018).

According to the cognitive reading model, reading comprehension is a skill that demands distinct cognitive processes (Jensen et al., 2011). The notion that empathy is one of the processes involved in reading comprehension is consistent with this model (Jensen et al., 2011). Additionally, without distinguishing affective from cognitive empathy, studies emphasize that reading fiction texts promotes empathy. Hence, reading helps elementary school children and adolescents to understand the perspective of others (Guarisco & Freeman, 2015), improving the student-teacher relationship (Bostic, 2014), and encouraging students to engage and, consequently, reach higher levels of reading comprehension and interpretation (Schonert-Reichl et al., 2015).

Factors concerning the reading of fiction texts that promote the development of empathy among elementary school students

The reading of narratives is associated with the development of prosocial behaviors, positively related to self-regulation and empathy among children, especially from the fourth grade onwards (Jensen et al. 2011). Hence, by reading and making connections with a story’s characters and their challenges, students start to perceive their own actions differently. This is especially true when the conflicts presented in a story are similar to elements present in the students’ context (Jensen et al. 2011).

According to a study conducted by Parsons (2013), reading fiction texts may lead children to establish different connections with a story’s characters: imagining themselves alongside these characters, wanting to help them; or imagining that they became these characters while still keeping their own identity. This process is even more intense when a narrative is described in the first person, and the narrator is the story’s main character. As a result of these connections with characters, elementary students engage in the reading of texts, developing and strengthening their ability to understand others’ points of view and developing their ability to make inferences, which is related to the cognitive component of empathy and contributes to improved performance in other disciplines as well (Parsons, 2013).

Furthermore, observing illustrations may help students to develop affective empathy, because they identify themselves emotionally with the characters’ happy/sad, positive/negative expressions/emotions (Karniol, 2012; Nikolajeva, 2012). In this context, the main emotions students in the early grades of elementary school identified in the stories were: joy, sadness, surprise, disgust, anger, and fear, which are basic emotions, considered universal by researchers from different cultures and times (Aram & Aviram, 2009; Karniol, 2012; Nikolajeva, 2012).

It is also noteworthy that from the fourth grade onwards, reading improves one’s vocabulary of emotions, which starts to encompass more complex emotional states, such as shame, distress, helplessness, compassion, among others (Lysaker & Sedberry, 2015). In addition, some studies report that from the fourth grade onwards, by developing empathy with fiction texts, students become less aggressive when discussing with peers with opinions different from theirs and manifest less prejudice and discriminatory behavior toward cultures that diverge from the dominant pattern (Lysaker & Sedberry, 2015; Lonigro et al. 2014).

Identifying perspectives on the relationship between reading and empathy

Thus far, the association between reading and empathy was mainly addressed by North American researchers from the United States and Canada (Bostic, 2014; Schonert-Reichl et al., 2015). Regarding Brazilian studies, the papers identified in national journals indexed in the databases were not only scarce but did not meet the inclusion criteria. Therefore, it shows a gap in the Brazilian context, i.e., there is a need for studies addressing the reading of fiction texts and the development of empathy.

Most of the studies addressing the topic considered in this review were intended to investigate whether empathy can be developed by reading fiction texts and contribute to the performance of students in text comprehension (Bostic, 2014; McTigue et al., 2015) and verify the factors that may be associated with empathy as a result of reading fiction texts (Brett, 2016). Most of the studies only collected the students’ self-reports to examine how empathy was developed by reading fiction texts (Venegas, 2019). Few studies included the teachers’ perceptions (Ness, 2019) or those of parents/legal guardians (Deschamps et al., 2014). Including parents and teachers' perspectives could contribute to understand the association between reading fiction texts and empathy, as they live with the children/adolescents and observe their behavior more closely.

Finally, it is essential to emphasize that there is not, thus far, a specific theory for the relationship between reading and empathy - there are theoretical perspectives that encourage research (Mar & Oatley, 2008; Mumper & Gerrig, 2017). Studies have addressed children (Merga, 2017), adolescents (Guarisco & Freeman, 2015), and adults in a college context (Mar & Oatley, 2008), and most of the studies addressing children intend to show the importance of including the development of empathy in the elementary schools’ curricula (Venegas, 2019), considering that social and emotional skills, especially empathy, promote various scholar benefits, among which, those related to learning to read and reading comprehension. It may also improve school climate and the relationship between teachers and students in class (Schonert-Reichl et al., 2015).

Final considerations

Considering the objectives proposed in this study and the results presented, some points should be highlighted. First, it is important to remember that this review’s timeframe includes studies published between 2009 and 2020 that address students attending elementary schools, their teachers, and parents/legal guardians. Second, the results show that the studies seldom focus on the relationship between reading fiction texts and empathy or whether reading and empathy mutually influence each other, though most studies consider the influence of reading on empathy. The effects of empathy on learning to read may vary, from facilitating literacy and promoting high performance in reading activities to achieving proficient reading comprehension in the final grades of elementary school. Additionally, it is important to highlight the studies’ conclusions: improved empathy levels obtained through reading fiction texts lead students to care more about their peers, as well as other people around them.

Regarding the affective and cognitive components of empathy, the studies showed that the interventions enable the development of both of them. Sometimes, the affective component is more strongly developed, and, in others, the cognitive one. Specifically, it seems that the affective component developed predominantly among children attending early grades. In this context, using texts with illustrations depicting the characters’ facial expressions improved the students’ ability to identify sadness, joy, surprise, fear, anger, and disgust. The cognitive component, in turn, was emphasized in the studies involving fourth-, fifth-, and sixth-grade students, mainly because, in these grades, the teaching program adopts different strategies to promote reading comprehension, such as the formulation of hypotheses and prediction of what might happen to the characters; empathy is a fundamental skill for students to understand points of view that diverge from their own.

The main studies found were interventions intending to develop empathy among students using specific teaching strategies, in addition to correlational studies, which intended to understand whether empathy predicts reading and how this relationship occurs in the different grades/stages of elementary schools. Case studies aimed to examine how teaching strategies involving reading and empathy would impact specific groups of students, deepening the understanding of these proposals through observations and interviews.

Finally, given the previous discussion, studies involving reading and empathy are needed in different cultural contexts, especially in Brazil, as there is a research gap. Future studies may provide a deeper understanding of the relationships between reading fiction texts and empathy in the educational context of elementary schools. Also, we suggest that policymakers consider this review’s results to (re)evaluate the reading of fiction texts to promote empathy and other socio-emotional skills, competencies that are essential for the coexistence and development of children and adolescents in educational contexts.

texto em

texto em