Bullying is a type of violence characterized by a power imbalance in which a person or group is exposed to different forms of intentionally aggressive acts repeatedly and over time (Olweus, 2013). The phenomenon was pioneeringly defined in this way by psychologist Dan Olweus based on research carried out in Nordic countries at the end of the 1960s (Limber, Breivik, & Smith, 2021). According to UNESCO, the prevalence of bullying varies across countries, but there is a consensus that it occurs on a global scale (UNESCO, 2019).

Recent estimates indicate that more than 50% of Nigerian schoolchildren engage in bullying (Umoke et al., 2020). A national study in Jordan found that 7.6% of students reported involvement in bullying as a bully (Shahrour, Dardas, Al-Khayat, & Al-Qasem, 2020). These two studies found boys to be more involved in school bullying than girls. In Brazil, the 2015 National School Health Survey (PeNSE), conducted with a sample of 102,301 schoolchildren from the final year of junior high school, found that 19.8% of students reported having engaged in bullying at school, corresponding to 24.2% among boys and 15.6% among girls (Silva et al., 2019). More recently, using data collected in 2019, the fourth edition of the PeNSE revealed a drop in the prevalence of bullying among Brazilian schoolchildren, from 20.4% to 12.0% (Malta et al., 2022). In another study in Brazil with 815 adolescents living in the state of São Paulo, 65.14% of boys and 23.16% of girls reported having perpetrated bullying (Garbin, Gatto, & Garbin, 2016).

These statistics reveal the seriousness of this problem and the disproportionate victimization and perpetration of bullying between the sexes. It is clear from the literature that the prevalence of bullying involvement is higher among boys than girls (Shahrour et al., 2020; Umoke et al., 2020). Studies also show that the type of peer aggression differs between sexes, with boys being more likely to engage in direct bullying (threats, insults, hitting, kicking, etc.) and girls tending to be involved in indirect or social bullying, such as spreading nasty rumors and social exclusion (Rose, Nickerson, & Stormont, 2015).

UNESCO’s Global Status Report on school violence and bullying (2019) suggests that schools may play an important role in maintaining differences between the sexes. Some schools, for example, instead of teaching empathy and gender equality, often do the opposite, reinforcing gender stereotypes and encouraging inequality and discrimination between girls and boys by handing out brochures with content naturalizing gender differences. This partially explains why boys tend to be more aggressive than girls, as from a young age they are encouraged by school, family, and society as a whole to adopt aggressive behavior that positively reinforces their masculinity. However, irrespective of gender differences, a large body of literature on this topic reveals the adverse impact of bullying on the health and development of all those involved in this type of violence. Moreover, students who bully are also prone to developing risk behaviors over time (Silva et al., 2016).

In view of the magnitude and adverse impacts of this problem, bullying is considered a public health problem and, to be effective, programs and interventions should take into account the characteristics of the actors involved, including aggressors and/or bystanders (UNESCO, 2019). Interventions should also consider issues related to observed differences between the sexes, since evidence shows that experiences of bullying differ considerably between boys and girls. However, literature reviews have yet to specifically address this topic. State-of-the-art literature reviews allow researchers to identify gaps in current knowledge and potential next directions for future research. In particular, the present study advances bullying research by synthesizing evidence addressed by theoretical studies, such as that conducted by Rose, Nickerson, and Stormont (2015).

In light of the above, this study aims to describe current evidence on the characteristics of boys and girls involved in bullying as aggressors.

Method

We conducted a literature review involving the following stages: topic identification and formulation of the guiding question; database search; study selection and assessment; data analysis; and presentation of the results. By systematically following these stages, the researcher can refine research topics or problems and perform a descriptive analysis of social and health issues to inform political decision-making or the adoption of professional practices (Silva, Brandão, & Ferreira, 2020). These stages followed the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist.

The guiding question was: What are the differences between boys and girls who bully reported in quantitative studies? This question was formulated using the SPIDER question framework, which helps define the following key elements of a review question: Sample, Phenomenon of interest, Design, Evaluation, and Research type (S = school-age boys and girls; PI = bullying; D = studies using quantitative designs or data; E = gender differences; R = quantitative primary studies.

Searches were performed for articles published between 2015 and 2020 in the following databases: SciELO, Scopus, Web of Science, and PsycINFO. Given the broad scope of the guiding question and the specific characteristics of each database, it was necessary to revise the search strategy used for each source. More specifically for SciELO, we did not use many descriptors: “bullying” AND “bullying at school” AND English OR Portuguese OR Spanish. For Scopus and PsycINFO, we used the descriptors and limiters “bullying” AND “aggressor” OR “attacker” OR “assaulter” OR “bully”. For Web of Science, we used the descriptors “bullying” AND “aggressor” OR “attacker” OR “assaulter “OR “bully”. The searches were performed in December 2020.

In the first stage of the article selection process, we screened the titles and abstracts of the studies found in each database, applying the following inclusion criteria: articles addressing bullying published in scientific periodicals during the period 2015-2020 written in Portuguese, English, or Spanish. Editorial pieces, letters, comments, review articles, mixed or qualitative studies, and studies that did not address the guiding question, included adult participants, or looked at bullying in contexts other than schools were excluded. Title and abstract screening were performed independently by two researchers (initials not shown).

In the next stage, the full-text versions of the selected articles were assessed and studies that did not adhere to the guiding question or failed to meet the inclusion criteria outlined above were removed. Articles written by the lead researcher (WAO) were also excluded. The latter coordinated, supervised, and validated the decisions taken during the assessment process and the definition of the corpus by the two reviewers.

To delineate the differences in experiences between boys and girls, we created a synoptic table to enable a descriptive and comparative analysis of the data. The main results of the review are presented in three categories: 1. Meta-theoretical analysis, presenting bibliometric data and outlining the theories and concepts used in the studies; 2. Meta-method analysis, including information on study procedures and the results of the methodological quality assessment; and 3. Meta-synthesis, bringing together current evidence on the characteristics of boys and girls involved in bullying. The methodological quality assessment was performed using the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross-sectional Studies, which consists of eight questions with the following response options: Yes, No, Unclear, or Not applicable (Moola et al., 2017). Studies are classified into one of three levels based on the scores obtained in the assessment: 1. High methodological quality and low risk of bias (7 or 8 points); 2. Moderate methodological quality and moderate risk of bias (between 5 and 7 points); and 3. Low methodological quality and high risk of bias (below 5 points).

Results and Discussion

Results

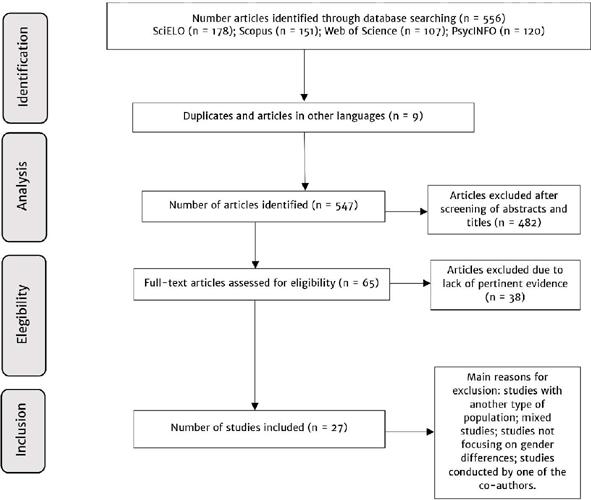

The database searches returned 547 records, 482 of which were excluded after screening the titles and abstracts. A further 38 articles were excluded after the full-text screening, resulting in a final review corpus of 27 studies. The study selection process is outlined in the flow diagram in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Flow diagram of the study selection process following the recommendation of the PRISMA checklist.

Category 1: Meta-theoretical analysis

Brazil accounted for the largest number of studies (n = 11), followed by Spain (n = 6), Portugal (n = 4), Colombia and Mexico (n = 2, each), and Albania, the United States, Sweden, and Nigeria (n = 1, each). It is important to highlight that the large number of studies found in Brazil does not necessarily mean that the output on the topic is greater in this country, but rather that the variables of interest were clearly spelled out in the article titles and abstracts. The years with the most publications were 2019 and 2017 (n = 11). The main area of expertise of the authors was psychology, psychiatry, nursing, and education; however, not all of the articles mentioned the authors’ academic background. Based on the information provided by the articles, most of the authors had a master’s degree or Ph.D. Some authors were involved in more than one of the selected articles. Table 1 presents the bibliometric data from the articles included in the review corpus and the main study results, which are explored further below.

Table 1 Main characteristics identified in the reviewed articles and highlighted results.

| Reference | Country; sample; age group | Highlighted results |

|---|---|---|

| Akanni et al., 2020 | Nigeria; n = 465; 16-19 years | Male students were twice as likely to be bullies as female students. This difference may be explained by cultural standards. |

| Bjärehed et al., 2019 | Sweden; n = 317; 10-15 years | Boys showed higher levels of use of moral disengagement mechanisms. |

| Garcés-Prettel, Santoya-Montes, & Jiménez-Osorio, 2020 | Colombia; n = 1,082; 14-18 years | Boys were involved more in bullying; in contrast, girls were more likely to receive insults from their parents and displayed poor communication with teachers. |

| Zequinão et al., 2020 | Brazil; n = 409; 8-16 years | Boys were more remembered, both in positive and negative terms, by classmates and enjoyed higher sociometric status. |

| Reisen, Viana, & Santos-Neto, 2019 | Brazil; n = 2,293; mean age 15-19 years | Boys were more involved in bullying as aggressors. |

| Dervishi, Lala, & Ibrahimi, 2019 | Albania; n = 284; 13-18 years | Both boys and girls involved in bullying as a victim or aggressors were prone to developing depression. Girls were more prone to experiencing emotional problems. |

| Dias, Rocha, & Mota, 2019 | Portugal; n = 351; 12-17 years | Boys tended to be more aggressive; however, sex did not moderate aggressive behavior in the adjusted analysis. |

| Romera et al. 2019b | Spain; n = 1,150; 6-11 years | Girls attributed blame to both aggressors and victims, while boys blamed only the victims. Female aggressors attribute more guilt and boys more indifference and pride. |

| Romera et al., 2019a | Spain; n = 1,339; 9-15 years | Boys enjoyed higher levels of popularity than girls in both classes with anti-bullying norms and pro-bullying norms. |

| Silva-Rocha et al., 2019 | Portugal; n = 2,623; 11-16 years | Boys were more likely to be bullies, engaging mainly in physical violence. Girls were more involved in verbal or indirect violence; girls who lived with neither of their parents were more likely to be aggressors than other girls. |

| Bosa et al., 2018 | Colombia; n = 354; 12-18 years | Boys were more likely to bully. Boys were more involved in direct bullying, while girls tended to engage in indirect bullying. |

| Estévez, Jiménez, & Moreno, 2018 | Spain; n = 1,510; 12-17 years | Aggressive behavior was significantly associated with high scores in depressive symptomatology, perceived stress and loneliness, and low scores in self-esteem, life satisfaction, empathy, academic engagement, and perceptions of family and school. Girls involved in bullying as aggressors had more negative attitudes towards the school and teachers than boys. |

| Machimbarrena & Garaigordobil, 2018 | Spain; n = 1,993; 9-13 years | No significant differences were found between the sexes, but boys reported engaging more in physical, psychological, and verbal abuse. |

| Marcolino et al., 2018 | Brazil; n = 678; 10-14 years | 8.4% of the participants reported having engaged in bullying; prevalence was higher among boys. Students who smoke and drink alcohol were 0.4 and 0.28 times more likely to bully. |

| Aguiar & Barrera, 2017 | Brazil; n = 76; 10-15 years | Physical abuse is the most common type of bullying in public schools and aggressors are mainly boys. In private schools, bullying tends to be more verbal and indirect; no gender differences were found. |

| González, 2017 | Mexico; n = 557; 8-16 years | The variable sex was independent from bullying. |

| Monteiro et al., 2017 | Brazil; n = 300; 8-17 years | Human values (mainly the interactive subfunction) may predict bullying behavior. The sex and age of participants were not statistically significant and therefore did not have a moderating effect. |

| Rosário, Candeias, & Melo, 2017 | Portugal; n = 80; mean age 12.65 years | Boys bully more than girls, engaging especially in physical bullying. |

| Silva & Costa, 2017 | Brazil; n = 5,300; age not informed | Boys bully more than girls. Individuals with higher socioeconomic status and mothers with a higher level of education were more likely to be involved in bullying. |

| Silva et al., 2017 | Brazil; n = 156; 11-16 years | No statistical difference was found; however, it was found that girls are more involved in indirect bullying, while boys engage more in direct bullying. Poor academic performance was associated with bullying. |

| Donoghue & Raia-Hawrylak, 2016 | US; n = 810; age not informed | Boys bully more than girls, engaging especially in physical bullying. Girls are more involved in social bullying. |

| Queirós & Vagos, 2016 | Portugal; n = 1,320; 10-18 years | Boys tend to be more aggressive, while girls tend to display more pro-social behavior. |

| Vega López & González Pérez, 2016 | Mexico; n = 1,706; 11-15 years | Boys are twice as likely as girls to engage in bullying; attention should be given to sociocultural roots. |

| Zequinão et al., 2016 | Brazil; n = 409; 8-16 years | Boys bully more than girls. Boys are more involved in physical bullying and girls in verbal or social bullying. |

| Fernández, Félix, & Ortega Ruiz, 2015 | Spain; n = 15 teachers; age not informed | Prevalence of bullying was higher among boys. Both low and high self-esteem are factors of risk for bullying behavior. |

| León-Del-Barco et al., 2015 | Spain; n = 700; mean age 13.98 years | Aggressors, especially boys, are more rejected or criticized by parents than non-aggressors. Boys are more involved in bullying as aggressors. |

| Serra-Negra et al., 2015 | Brazil; n = 366; 13-15 years | Boys are more involved in verbal bullying; aggressors display a low level of personal satisfaction and are more likely to be from better off families. |

Notes: n = number of study participants.

In general, the authors adopted Dan Olweus’ classic definition of bullying. The theoretical approach adopted varied according to each study objective, with studies drawing mainly on social learning theory, social control theory, and social cognitive theory. However, few studies used theoretical frameworks to analyze the results, with most examining the problem by comparing findings with the results of other studies. Investigations that addressed verbal bullying characterized this form of violence basically as insults, name calling, and threats, with engagement in this type of bullying being more prevalent in boys.

Category 2: Meta-method analysis

Study data were collected using self-report instruments completed by middle and high school students, such as questionnaires or scales. Study participants were selected using convenience sampling methods, predominantly non-probability sampling. Most of the studies used statistics software packages for data analysis, the most common being SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Science) in its different versions. Various types of statistical analysis procedures were employed, including the chi-squared test, ANOVA, logistic regression, and bivariate and multivariate analysis.

The results of the methodological quality assessment are presented in Table 2. Two studies were found to have a high level of methodological quality and low risk of bias (Bjärehed, Thornberg, Wänström, & Gini, 2019; Queirós & Vagos, 2016). The rest were rated as having moderate methodological quality and moderate risk of bias.

Table 2 Results of the methodological quality assessment.

| Reference | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akanni et al., 2020 | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |||

| Bjärehed et al., 2020 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 8 |

| Garcés-Prettel et al., 2020 | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |||

| Zequinão et al., 2020 | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |||

| Dervishi et al., 2019 | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |||

| Dias et al., 2019 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 | ||

| Reisen, Viana, & Santos-Neto, 2019 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 | ||

| Romera, Bravo et al., 2019 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 | ||

| Romera, Ortega-Ruiz et al., 2019 | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |||

| Silva-Rocha et al., 2019 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 | ||

| Bosa et al., 2018 | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |||

| Estévez, Jiménez, & Moreno, 2018 | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |||

| Machimbarrena & Garaigordobil, 2018 | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |||

| Marcolino et al., 2018 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 | ||

| Aguiar & Barrera, 2017 | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |||

| González, 2017 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 | ||

| Monteiro et al., 2017 | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |||

| Rosário, Candeias, & Melo, 2017 | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |||

| Silva & Costa, 2017 | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |||

| Silva et al., 2017 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 | ||

| Donoghue & Raia-Hawrylak, 2016 | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |||

| Pérez & López, 2016 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 | ||

| Queirós & Vagos, 2016 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 7 | |

| Zequinão et al., 2016 | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |||

| Fernandez et al., 2015 | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |||

| León-Del-Barco et al., 2015 | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |||

| Serra-Negra et al., 2015 | X | X | X | X | X | 5 |

Notes: Q1 = Were the criteria for inclusion in the sample clearly defined? Q2 = Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail? Q3 = Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way? Q4 = Were objective, standard criteria used for measurement of the condition? Q5 = Were confounding factors identified? Q6 = Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? Q7 = Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way? Q8 = Was appropriate statistical analysis used?

The main methodological weaknesses observed in the studies were as follows: lack of information on confounding factors (factors which may distort actual associations between the exposure of interest and study outcome) and strategies used to deal with them; and not clearly defined inclusion criteria. Other weaknesses were also highlighted by the authors themselves as study limitations, including: limitations inherent to the cross-sectional study design used by most of the studies; the use of self-report instruments for data collection, which increases the risk of social desirability bias; and small sample size.

Category 3: Meta-synthesis

All the selected studies demonstrate, to a greater or lesser extent, differences between the sexes for school bullying involvement. The studies unanimously confirm that boys are more likely than girls to be bullies (Bosa et al., 2018; León-del-Barco, Felipe-Castaño, Polo-del-Río, Fajardo-Bullón, 2015; Silva-Rocha, Soares, Brochado, & Fraga, 2019; Zequinão, Medeiros, Pereira, & Cardoso, 2016), with some studies showing an almost twofold difference in magnitude (Akanni, Olashore, Osasona, & Uwadiae, 2020; Vega López & González Pérez, 2016). The main results of the reviewed articles are synthesized in Table 1 above.

Boys are more likely to engage in direct bullying (physical or verbal) and girls are involved more often in indirect bullying (social exclusion, spreading gossip and rumors) (Bosa et al., 2018; Silva et al., 2017). Boys are more likely than girls to be involved in physical aggression (Donoghue & Raia-Hawrylak, 2016; Silva-Rocha et al., 2019; Zequinão et al., 2016). One study found that boys were more involved in verbal bullying than girls (Serra-Negra et al., 2015); however, evidence in the literature shows that this type of violence tends to be more common among girls.

In general, the findings show that aggressors of both sexes display symptoms of depression, perceived stress, feelings of loneliness, low self-esteem, and low life satisfaction (Estévez, Jiménez, & Moreno, 2018). Both boys and girls involved in bullying as a victim or aggressor are prone to developing depression, while girls are more likely to experience emotional problems such as anhedonia and low self-esteem (Dervishi, Lala, & Ibrahimi, 2019). In contrast, Fernández, Félix, and Ortega Ruiz (2015) found that both positive and low self-esteem were risk factors for bullying behavior, possibly because self-esteem is an unstable personality trait. Other studies showed that boys tend to be more aggressive (Dias, Rocha, & Mota, 2019; Queirós & Vagos, 2016), while girls tend to display a more pro-social behavior (Queirós & Vagos, 2016), which may be a protective factor against becoming a bully. Furthermore, girls tend to value closeness and intimacy in their social relationships (Queirós & Vagos, 2016).

Bullies tend to have a negative perception of school and poor academic performance (Estévez, Jiménez, & Moreno, 2018; Silva et al., 2017). In contrast, they enjoy higher social status and are more likely to be picked for teams in physical education classes and less likely to be chosen for in-class activities (Zequinão et al., 2020). Another study showed that boys enjoyed higher levels of popularity than girls in both classes with anti-bullying norms and classes with pro-bullying norms (Romera, Bravo, Ortega-Ruiz, & Veenstra, 2019a). Girls involved in bullying as aggressors are less involved in school activities and display poorer communication with teachers in comparison with boys (Estévez, Jiménez, & Moreno, 2018; Garcés-Prettel, Santoya-Montes, & Jiménez-Osorio, 2020). It is interesting to note that male public school students were more likely than male private school students to engage in bullying and physical aggression. Differences between the sexes were not observed in private schools and the most common types of bullying in this setting were verbal and indirect (Aguiar & Barrera, 2017).

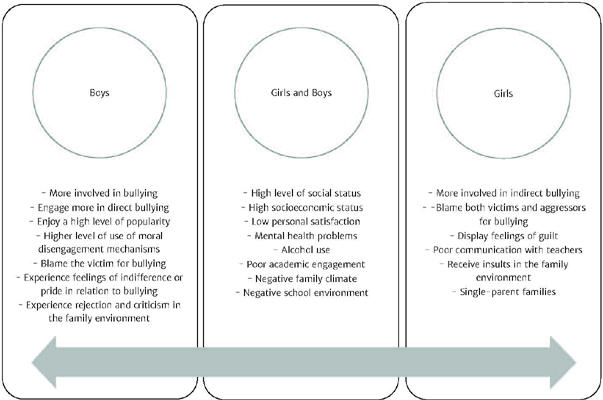

Studies also showed that bullies had a negative perception of the family environment, which was marked by parental rejection and criticism (Estévez, Jiménez, & Moreno, 2018; Leóndel-Barco et al., 2015). Boys were more likely to receive parental criticism (León-del-Barco et al., 2015), while girls tended to receive insults (Garcés-Prettel, Santoya-Montes, & Jiménez-Osorio, 2020). Furthermore, girls who lived with neither of their parents were more likely to be aggressors than other girls (Silva-Rocha et al., 2019). Boys also tended to score higher than girls for moral disengagement mechanisms (Bjärehed et al., 2020). Concerning emotional expression, female aggressors tended to feel more guilt, while male aggressors reported feelings of indifference and even pride (Romera, Ortega-Ruiz, Rodríguez-Barbero, & Falla, 2019b). Figure 2 synthesizes the main characteristics of boys and girls who engage in school bullying.

Discussion

The quantitative research designs used by the studies analyzed in this review help understand and estimate the magnitude of individual and contextual influences that contribute to school bullying. Boys were more involved than girls in bullying and were more likely to engage in physical bullying, while girls used more subtle or indirect modes of abuse, resorting to internalizing behaviors. Family factors, such as repeated experience or exposure to domestic violence, poor communication, and structural influences, were also associated with bullying involvement. While both male and female aggressors obtained good scores for social adjustment, bullying is a risk factor for negative health behaviors. Thus, contrary to expectations, bullying is associated with adverse impacts on the adjustment process for both victims and aggressors.

Male aggressiveness, illustrated by the disproportionate involvement of boys in bullying and their tendency to engage in externalizing behaviors, has been widely documented in the literature since the emergence of pioneering studies on the phenomenon. While there is a tendency to attribute men’s higher propensity for violence to biological factors, this behavior can also be explained by cognitive characteristics. Although negative cognitions and emotions have been routinely associated with male violence, positive cognitions such as optimism and selfconfidence can also increase the chance of aggressive behavior (Cabral et al., 2020). This may explain why bullies score higher for perceived popularity (Guy, Lee, & Wolke, 2019).

In contrast, girls tend to learn empathetic behaviors during their process of socialization, such as care and affection, while boys are trained to be dominant and expected to display physical strength and superiority, often using violence to this end, which can become a risk factor for school bullying (Espinosa, Martínez, & Tarrés, 2021). Female aggressors were also more likely to experience feelings of sadness, shame, and demotivation (Sampaio et al., 2015). The characteristics of girls mean they are more likely to garner sympathy, social support, and help, especially from the family (Zequinão et al., 2020). However, the present review found that female aggressors also experience negative family environments with high levels of conflict, which can weaken their sense of security and support. Differences between boys and girls can also have sociocultural roots, as traditionally aggressive male behavior is reinforced by society, while girls are expected to be sensitive, control their emotions, and avoid conflict (Silva et al., 2013).

Although the literature has documented differences between boys and girls for bullying, this review also reveals some characteristics that are common to both sexes. Considering the increased involvement of boys in social and cyberbullying and the increasing tendency for girls to engage in physical bullying, further research is required to investigate changes in bullying patterns. Studies drawing on critical and social theories suggest that dramatic changes are taking place in gender identity or expression during adolescence, which in turn have an impact on the (re)production of violence. This hypothesis should also be addressed by future research on bullying.

About negative perceptions of school among boys and girls, lower rates of bullying were observed in schools where the climate was perceived to be favorable (Hultin et al., 2021). In the present review, girls displayed more negative attitudes towards the school than boys. It is as if students cannot trust the school to provide a safe environment. One explanation for this finding is that students may display reactive aggressive behavior as a response to an environment perceived as hostile and that fails to satisfy students’ needs. On the other hand, studies found that a large number of girls lived in families without the presence of at least one parental figure. This aspect should be investigated by future research on bullying by girls, especially considering the reality in Brazil and the multiple forms of family structure in the country.

In another direction, the studies show that, while bullying takes place at school, family factors are also associated with this phenomenon. One study revealed that living in a dysfunctional family with a poor family and couple communication can increase the likelihood of school bullying involvement. Being part of an unstable family weakened by interpersonal conflicts is a risk factor for school bullying involvement, which is consistent with the literature (Kretschmer, Veenstra, Deković, & Oldehinkel, 2017). The findings of this review show that the family climate was overwhelmingly negative for both boys and girls involved in bullying as aggressors. These findings suggest that interventions should also focus on the family, seeking to improve communication skills and discipline to strengthen family bonds and promote respectful dialogue.

This review provides a broader insight into the consequences of bullying since a large proportion of the selected studies place particular emphasis on the impacts of abuse on victims. In this sense, a study in Turkey with 456 adolescents revealed that bullies also reported diminished subjective well-being and greater emotional and behavioral problems both inside and outside school compared with non-involved peers. In addition, students who engage in bullying may also become involved in violence at other moments in the life cycle (Silva et al., 2016), illustrating the preventive dimension of early intervention in cases of bullying.

The evidence found has practical implications that warrant highlighting. It is important to understand that bullying is a multi-faceted phenomenon and that gender can have a moderating effect on aggressive behavior among students. At an individual level, schools and education professionals can use the findings of this review to promote the development of socio-emotional skills in boys, such as empathy and solidarity. Concerning girls, it is important to value their feelings and facilitate the development of a sense of belonging to the school community. Interventions should also focus on issues related to the mental health of individual aggressors. From a contextual perspective, families should receive guidance on non-violent communication and specific programs should be implemented to support the development of strong family bonds that increase the subjective well-being of students of both sexes.

Final Considerations

School bullying is a specific form of violence that affects the health and emotional and cognitive development of students. Aggressors also suffer from the consequences of bullying involvement and this review focused on studies addressing the characteristics of these students, providing a picture of gender differences found in the literature and thus gaining further insight into the nuances of this issue. The findings of the selected studies reveal that boys and girls involved in bullying as aggressors engage in different forms of abuse and both groups have a negative perception of the school environment and family climate. While the prevalence of bullying is higher in boys, this finding should be interpreted with caution, as the evidence shows that boys may be more likely to admit to engaging in aggressive behavior to show off to their peers, increasing their social “prestige”. It was also found that certain family characteristics may be risk factors for bullying. Thus, this review makes an original contribution to current knowledge on this topic by mapping evidence on the characteristics that differentiate boys and girls involved in school bullying.

This review has some limitations. First, the results of the methodological quality assessment showed that most studies had moderate methodological quality and a moderate risk of bias. Second, it was not possible to encompass all publications on the topic and studies that did not explicitly mention the characteristics of students involved in bullying in the title and abstract were excluded during screening. Third, not all the studies aimed to demonstrate differences between the sexes for bullying or describe student characteristics. Finally, the review did not control for different gender identities, with the analysis being performed based on the biological sex declared by the participants in the reviewed studies.

Directions for future research include studies focusing specifically on differences between the sexes for involvement in bullying. Qualitative research should also be encouraged in order to gain a deeper understanding of the phenomenon and its complexities from the perspective of boys and girls who engage in bullying. Furthermore, longitudinal studies could help broaden understanding of differences and similarities between sexes and the impact of changes in family structure on this type of behavior at school. This review may also be considered a starting point for informing anti-bullying interventions geared toward aggressors, addressing gender differences, which appear to moderate the type of bullying perpetrated by students.

texto em

texto em

Curriculum ScienTI

Curriculum ScienTI