Sports excellence involves several facets related to physical, technical, tactical, and psychological preparation to achieve a desirable athletic performance (Llewellyn et al., 2008; Nascimento Junior et al., 2014). Because even subtle differences in an athlete’s preparation and performance can result in their success or failure in competitions (Machado, 2018), an analysis of the factors that can influence the performance of high-performance athletes is of great relevance (Leo et al., 2015; Nascimento Junior et al., 2016).

Among the psychological factors, self-efficacy plays a key role (Shoenfelt & Griffith, 2008) because an athlete’s belief in their ability to take the course of action necessary to achieve a specific goal (Bandura, 1989) facilitates the adherence, maintenance, persistence, motivation, and effort they demonstrate (Valiante & Morris, 2013). However, how athletes assess themselves concerning their thinking patterns and how they behave to achieve their goals fluctuates within the same environment (Bandura, 1990) and may affect their behavior differently (Barker et al., 2013; Feltz et al., 2008).

Because activity domains vary in breadth and complexity, athletes’ self-efficacy seems to be affected not only by personal variables (e.g., sex, age, practice time, personality, task familiarization, regulation of motivation, thought processes, performance level, and emotional states); (Machado et al., 2021), but also by aspects external to the individual (e.g., changes in environmental conditions, type of competition, location of the games, opponents, or the position the athlete plays) (Bandura, 1989; Beattie et al., 2014; Hofseth et al., 2017; Machado, 2018; Machado et al., 2018; Mouloud & Elkader, 2017; Rodríguez et al., 2015; Sarmento et al., 2014). It is, therefore, evident that the relevant types of self-efficacy and their assessment also depend on the scope of the activity (Bandura, 2012).

Accordingly, as the literature suggests, not all athletes possess the same levels of self-efficacy; neither do all questionnaires assess self-efficacy similarly, as indicated by systematic reviews (Machado et al., 2014; 2018). For instance, the self-efficacy questionnaire used in the current research differentiates between Self-Efficacy in the Game, Defensive Self-Efficacy in Volleyball, and Offensive Self-Efficacy in Volleyball. The Self-Efficacy in the Game dimension predominantly includes general aspects common to the self-efficacy of volleyball athletes related to the technical, tactical, and psychological elements inherent to the game. The Defensive Self-Efficacy in Volleyball and Offensive Self-Efficacy in Volleyball dimensions, which are characterized mainly by technical and tactical aspects, demands specific skills and knowledge according to the offensive and defensive functions of high-performance athletes that are relevant to their sports performance according to their functions on the court (Machado, 2018). This suggests that, in certain positions, more than one type of efficacy is necessary to achieve good performance.

As previously stated, one aspect that seems to have more influence on athletes’ self-efficacy levels involves the specific demands of each game position. The athletes’ positions are essential, given that they have unique demands regarding skills and knowledge during the matches. Studies reviewed by Sarmento et al. (2014) concerning soccer athletes demonstrated that physical and technical demands differ depending on the player’s position on the field. For example, attackers present a high estimate of their ability to be adaptable because these athletes are usually close to their goal in offensive situations and away from their goal in a defensive situation. This means that, compared with players in other positions, they may have more to gain by attempting dangerous actions with a low probability of success than they will have to lose if they are unsuccessful (Hofseth et al., 2017). Authors and partners (Ortega et al., 2009) investigated young basketball players’ performance and participation indicators during competition. They found that performance and participation variables differentiated players with high and low levels of self-efficacy. Players with high levels of self-efficacy showed higher values in different performance variables, including points scored, shot attempts, 1, 2, and 3-point shots, personal highs received and minutes of participation played, total ball possession time, number of ball possessions, number of passes received, and number of offensive phases in which the player participated compared to players with low levels of self-efficacy. Ortega and collaborators, in one unit of a physical education class, found that the use of an adapted basket height allowed 13-year-old children to develop better shooting techniques, improved student participation in shooting and the effectiveness of their shots, and increased specific individual self-efficacy (Ortega et al., 2020).

Little is known, however, about how technical and tactical aspects influence the beliefs of Brazilian volleyball athletes (Oliveira et al., 2018). A recent systematic review (Machado et al., 2018) revealed that most studies of self-efficacy in volleyball athletes contemplated attributes related to technical aspects without considering how the position that athletes play on the court influenced their self-efficacy.

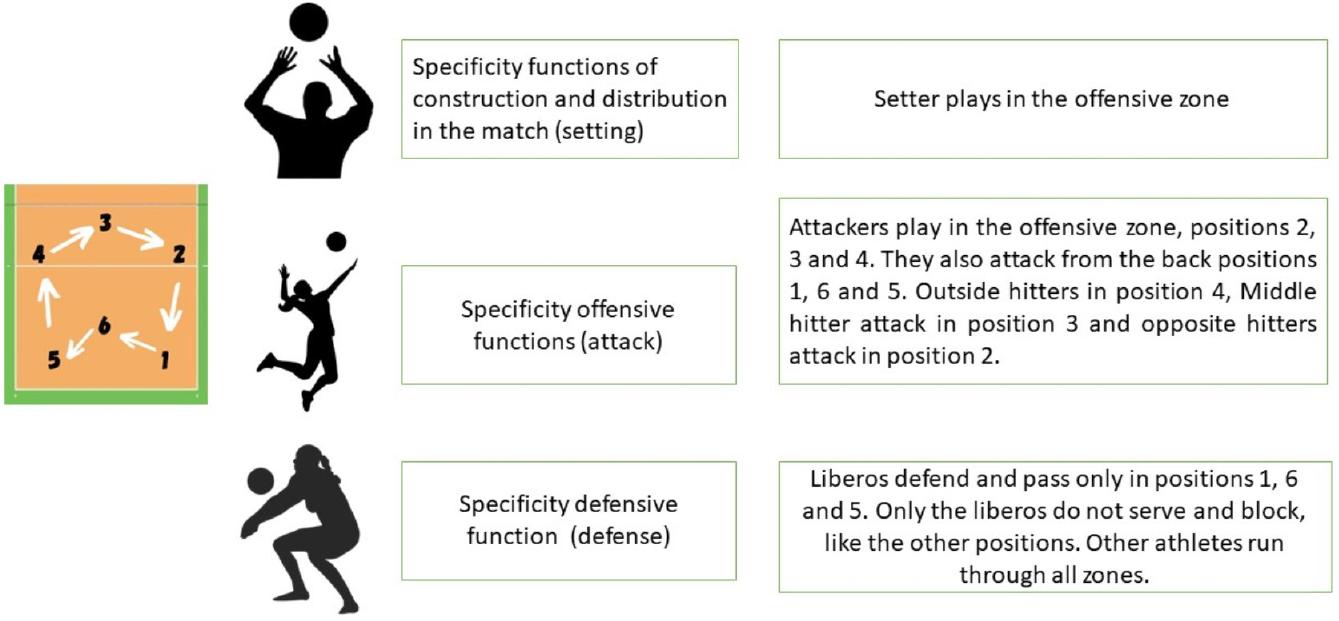

In the specific case of high-performance volleyball, the position that athletes play, along with other elements, such as playing at home or away from home, the presence of spectators, and the characteristics of the opponents, among others, seem to influence various aspects of the game, including the athletes’ view of themselves and their sporting performance. However, self-efficacy studies in this modality have predominantly investigated technical aspects without considering other facets (Machado et al., 2018). Concerning volleyball, five positions perform specific functions on the court and involve different physical, technical, tactical, and psychological requirements: (a) setters, (b) liberos, (c) outside hitters, (d) middle hitters, and (e) opposite hitters. The setter is responsible for distributing the plays, making quick decisions, and assuming greater responsibilities regarding team strategies (Matias & Greco, 2011; Palao et al., 2005; Palao & Manzanares, 2009; Resende, 1995). Hitters are responsible for defining the play. The libero is responsible for passing and defending throughout the match (Costa et al., 2016; Matias & Greco, 2016). Among the hitting positions, the main functions of the middle hitter are to attack fastballs and block (Matias & Greco, 2009), while the opposite hitter defines important balls of the match, and the outside hitter executes the passes and attacks (Costa et al., 2016; Marcelino et al., 2014). Therefore, it is necessary to consider that an athlete’s belief in their ability to perform a given action demands successful thought processes, performance levels, and emotional states consistent with the required attributes (Bandura, 2012). Accordingly, it is plausible to expect that position-related demands may influence how athletes develop their beliefs about what they can perform. The Self-Efficacy in the Game dimension may, therefore, require a higher level of self-efficacy because this covers common aspects of the self-efficacy of volleyball athletes. In contrast, the offensive and defensive self-efficacy dimensions cover more specific behaviors depending on the demands of the particular positions.

Given the importance of the self-efficacy of elite players regarding their performance, as well as the possible impact of the demands that a particular position exerts on the self-efficacy of athletes who play in highly competitive environments, the low amount of attention that has traditionally been paid to high-performance volleyball, and the lack of studies that bring it all together in the context of Brazilian sport, we sought to fill this gap by analyzing the association between self-efficacy and game position in high-performance Brazilian volleyball athletes.

We proposed four hypotheses:

Dimension 1, Self-Efficacy in the Game, will be the dimension where the setters present the highest self-efficacy values.

Dimension 2, Defensive Self-Efficacy in Volleyball, will be the dimension where liberos present the highest self-efficacy values.

Dimension 3, Offensive Self-Efficacy in Volleyball, will be the dimension where the attackers (outside, middle, and opposite hitters) obtain the highest self-efficacy values.

Global Self-Efficacy in Volleyball will be the dimension where outside hitters obtain the highest means.

Method

Participants

The sample comprised 300 high-performance athletes from the Brazilian Superliga (133 men and 167 women), including 75 middle hitters, 45 opposite hitters, 92 outside hitters, 50 setters, and 38 liberos, considered a representative sample of high-performance volleyball athletes. Their mean age was 24.88 years (SD = 5.51, range = 16-41), and they had been participating in their sport for a mean of 11.12 years (SD = 5.24, range = 2-30). To improve the visualization of the participants, Figure 1 presents the athletes’ positions according to their functions on the court. All clubs that participated in the main competition at the national level were invited, aiming to include the maximum number of high-performance athletes. Those athletes who were released by the clubs and agreed to participate were included in the study. They came from the South, Southeast, and Central-West regions in Brazil, as these regions had teams participating in the Superliga and were identified by the positions in which they played. There were about 400 athletes enrolled in the competition, in both suits, in the season.

Procedure

The principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, 2013) were followed, emphasizing the anonymity of the data collected, the confidentiality of the participants, and nondiscrimination against them. The participants and tutors (parents or coaches) who agreed to participate in the study were personally invited to read and sign a consent form. The study was approved by the Health Sciences Sector (SCS) Research Committee (authorization No. 1.574,.185).

Data collection took place between October 2016 and March 2017 in the gyms where the athletes trained, before or after practice, according to the availability of each team. The average time the athletes spent completing the instrument was 12 minutes.

Instrument: The Volleyball Self-Efficacy Scale

The Volleyball Self-Efficacy Scale (VSES (Machado, 2018)) evaluates efficacy expectations by measuring the strength of an athlete’s belief in their ability to perform the activities required by their position. Respondents rated the strength of their belief in their ability to perform each position-related skill during volleyball matches effectively on a scale that ranged from 0 to 100 (with unit intervals of 10), in which 0 corresponded to nothing (i.e., the athlete does not believe in their ability), 50% corresponded to moderately (indicating a moderate degree of belief in their ability), to 100% completely (when the individual is completely convinced of their capacity to fulfill their role). The instrument is composed of 19 items distributed in the following three dimensions. Dimension 1, Self-Efficacy in the Game (e.g., ‘Recovering quickly from an error’), includes 12 items, Dimension 2, Defensive Self-Efficacy in Volleyball (e.g., ‘Being able to guide the team and command the deep court’), four items, and refer to Dimension 3, Offensive Self-Efficacy in Volleyball (e.g., ‘Defining a difficult point’), three items. The VSES allows researchers to obtain a mean score for each dimension and a total instrument score (Global Self-Efficacy in Volleyball). Overall, the instrument has good psychometric properties (χ2 = 447.78, df = 148; Satorra-Bentler χ2 = 354.20, p < .05; root-mean-square error of approximation = .08, non-normed fit index = .90, comparative fit index = .92, incremental fit index = .92; and α = .92, Ωt = .97 regarding overall reliability).

Statistical Analyses

We analyzed the athletes’ self-efficacy through a one-way analysis of variance and Tukey’s post hoc test. The IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 22, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) software was used. The G-Power (Version 3.1, Heinrich Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany) software calculated effect sizes and statistical power.

Results

First, the principal descriptions for the total sample were calculated. The main self-efficacy scores, in the different dimensions of the questionnaire and the total scale score, indicated that the highest mean scores were in Self-Efficacy in the Game (M = 78.94, SD = 13.02) and followed by Defensive Self-Efficacy in Volleyball (M = 73.12, SD = 20.24). In contrast, the lowest means were for Offensive Self-Efficacy in Volleyball (M = 73.59, SD = 25.62). The mean for Global Self-Efficacy in the Game was 75.22 (SD = 14.53; see Table 1).

Table 1 Scores on the Volleyball Self-Efficacy Scale.

| Player Position | n | M | SD/ Tukey’s |

F | p | η | Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension 1: Self-Efficacy in the Game | |||||||

| Middle hitter (a) | 75 | 76.37 | 12.37d | 2.34 | .5 | 2.28 | 1.00 |

| Opposite hitter (b) | 45 | 78.57 | 14.28 | ||||

| Outside hitter (c) | 92 | 78.40 | 12.96 | ||||

| Setter (d) | 50 | 83.40 | 13.23a | ||||

| Libero (e) | 38 | 79.89 | 11.61 | ||||

| Total | 300 | 78.94 | 13.02 | ||||

| Model fixed effects | 12.91 | ||||||

| Dimension 2: Defensive Self-Efficacy in Volleyball | |||||||

| Middle hitter (a) | 75 | 55.93 | 21.58b, c, d, e | 30.15 | .01 | 10.89 | 1.00 |

| Opposite hitter (b) | 45 | 72.56 | 19.72a, e | ||||

| Outside hitter (c) | 92 | 78.12 | 14.65a, e | ||||

| Setter (d) | 50 | 77.95 | 16.07a,e | ||||

| Libero (e) | 38 | 89.28 | 9.30a, b, c, d | ||||

| Total | 300 | 73.12 | 20.24 | ||||

| Model fixed effects | 17.17 | ||||||

| Dimension 3. Offensive Self-Efficacy in Volleyball | |||||||

| Middle hitter (a) | 75 | 80.84 | 16.34d, e | 45.26 | .01 | 15.76 | 1.00 |

| Opposite hitter (b) | 45 | 85.56 | 15.11d, e | ||||

| Outside hitter (c) | 92 | 83.88 | 13.49d, e | ||||

| Setter (d) | 50 | 58.67 | 24.51a, b, c, e | ||||

| Libero (e) | 38 | 39.82 | 35.17a, b, c, d | ||||

| Total | 300 | 73.59 | 25.62 | ||||

| Model fixed effects | 20.30 | ||||||

| Global Self-Efficacy in Volleyball | |||||||

| Middle hitter (a) | 75 | 71.05 | 14.86b, c | 7.02 | .01 | 4.27 | 1.00 |

| Opposite hitter (b) | 45 | 78.90 | 13.65a, e | ||||

| Outside hitter (c) | 92 | 80.13 | 11.94a, d, e | ||||

| Setter (d) | 50 | 73.34 | 15.19c | ||||

| Libero (e) | 38 | 69.67 | 15.40b, c | ||||

| Total | 300 | 75.22 | 14.53 | ||||

| Model fixed effects | 13.98 | ||||||

Note. Items that indicate differences between the positions are identified by the letters a (middle hitter), b (opposite hitter), c (outside hitter), d (setter), and e (libero) in Tukey’s post hoc test.

To investigate the differences in the responses to the different dimensions of the VSES scale and in the total scale scores according to positions (setter, outside hitter, middle hitter, opposite hitter, and libero), we conducted a one-way analysis of variance and a Tukey post hoc test (see Table 1). The results showed significant differences (p < .05) in the athletes’ self-efficacy according to the game positions for the following dimensions: Defensive Self-Efficacy in volleyball (F = 30.15, p < .01, η = 10.89), Offensive Self-Efficacy in Volleyball (F = 45.26, p < .01, η = 15.76), and Global Self-Efficacy in Volleyball (F = 7.02, p < .01, η = 4.27).

Regarding Dimension 1, Self-Efficacy in the Game, we noted a significant difference only between players who acted as middle hitters and setters, with higher self-efficacy among the setters (M = 83.40, SD = 13.23) compared with the middle hitters (M = 76.37, SD = 12.37). Dimension 2, Defensive Self-Efficacy in Volleyball, showed that middle hitter and libero players differed significantly in their perceptions of self-efficacy from the other positions, and opposite hitters and setters differed from middle hitter and libero players. Higher self-efficacy was found for liberos (M = 89.28, SD = 9.30), and lower self-efficacy was found for middle hitters (M = 55.93, SD = 21.58). Considering Dimension 3, Offensive Self-Efficacy in Volleyball, all attack positions (middle hitter, opposite hitter, and outside hitter) showed significant differences (p < .05) in the players’ self-efficacy with the setter and libero positions, with greater self-efficacy found for opposite hitters (M = 85.56 SD = 15.11), and lower self-efficacy was noted in liberos (M = 39.82, SD = 35.17). In addition, the liberos and the setters differed from all attacking positions, scoring lower in relation to the attackers.

In Global Self-Efficacy in Volleyball, there were significant differences (p < .05) between (a) middle hitters (M = 71.05, SD = 14.86) and opposite (M = 78.90; SD = 13.65) and outside hitters (M = 80.13, SD = 11.94); (b) opposite hitters (M = 78.90, SD = 13.65) and middle hitters (M = 71.05, SD = 14.86) and liberos (M = 69.67, SD = 15.4); (c) outside hitters (M = 80.13, SD = 11.94) and middle hitters (M = 71.05, SD = 14.86), setters (M = 73.34, SD = 15.19), and liberos (M = 69.67, SD = 15.40); (d) setters (M = 73.34, SD = 15.19) and outside hitters (M = 80.13, SD = 11.94); and (e) liberos (M = 69.67, SD = 15.40) and opposite (M = 79.90, SD = 13.65) and outside hitters (M = 80.13, SD = 11.94). Outside hitters had the highest self-efficacy scores (M = 80.13, SD = 11.94), while the liberos scored lowest in self-efficacy (M = 69.67, SD = 15.40).

Discussion

This study aimed to analyze the self-efficacy of high-performance Brazilian volleyball athletes according to their playing positions and specifically to examine whether a particular position is associated with the dimension of self-efficacy to a greater degree than other positions according to the functions related to a specific position.

In analyzing the dimensions of the VSES, greater self-efficacy was observed in Dimension 1, Self-Efficacy in the Game, which can be understood by the fact that most of the items that make up this dimension (e.g., Item 2, ‘Maintain control and stability of your function at different points in the game’; Item 3, ‘Make quick decisions to define action strategies’; and Item 15, ‘Overcome difficulties in the match and believe that it is possible’); evaluate general aspects, including behaviors such as emotional control, patience, thought control, and so on, regardless of the positions the athletes play.

In general, the highest mean self-efficacy values in Dimension 1 were found for the setters, possibly because of the tactical intelligence required to perform this role. Because they are considered essential players in terms of the tactical and offensive strategic development of the match, they are considered the ‘brain of the team’ (Matias & Greco, 2016; Palao et al., 2004; Resende, 1995), and they must quickly process a large amount of varied information to make critical offensive decisions (Mesquita & Graça, 2002; Mesquita, 2002). The following items of Self-Efficacy in the Game reflect these functions: Item 7, ‘Realize what is happening in your team and with the opposite team during the match’; Item 14, ‘Be focused to distinguish what to do at specific times in the match’; and Item 15, ‘Overcome difficulties in the match and believe that it is possible.’ The findings reinforce the vital role setters play in assuming greater responsibility for the team’s tactical strategies, deciding the number of hitters to use in the team’s attack system, determining the course of these players’ movements, monitoring the speed used in the performance of each of these attackers, and observing how the blocking and defensive system of the opponents are positioned (Matias & Greco, 2011). As distributors of team play, the setters define their team’s offensive movement and are responsible for framing the attack (Matias & Greco, 2009; Mesquita, 2002; Palao et al., 2004). In addition, the setter’s decisions regarding the offensive structure of their team require knowledge about the characteristics, conditions, techniques, tactics, and psychology of the attackers with whom the setter is engaging (Matias & Greco, 2016). Therefore, Hypothesis 1 can be accepted because the setters presented the highest self-efficacy scores thanks to their tactical intelligence.

Dimensions 2 and 3, Offensive and Defensive Self-Efficacy in Volleyball, respectively, presented similar means in all the game positions, which was expected because these dimensions represent predominantly technical-tactical aspects related to the roles that athletes perform on the court (Marques et al., 2008). As Bandura (2006) suggested, individuals’ beliefs in their capacities vary according to the domains of situational activities and conditions rather than manifesting themselves uniformly in tasks and contexts. As the positions the athletes play are physical aspects recognizable as part of the group structure, they create behavioral expectations and specific interactions among group members (Eys et al., 2019), with offensive actions (serving, attacking, and blocking), attack structures (reception and defense), and defensive actions (block and defense) that demand specific qualities in the athletes performing these actions (Marcelino et al., 2010).

Regarding Dimension 2, Defensive Self-Efficacy in Volleyball, all items (Item 5, 'Be able to guide your team and command the defensive court zone'; Item 6, 'Able read the defensive court zone'; Item 8, 'Save a tipped ball'; and Item 18, 'Demonstrate the courage to stand and defend') reflect defensive behaviors in a volleyball game. Defense is considered the sole foundation common to all positions. However, some positions have it more or less often according to the nuances of the position (Collet et al., 2011) and the athletes’ characteristics (Mesquita et al., 2007). The libero position is characterized by passing and defending throughout the match and, as expected, in general, the libero participants had a higher perception of self-efficacy than all other positions in the Defensive Self-Efficacy in Volleyball domain. Liberos, who function in a defense capacity, may increase the use of second-ball attacks in counterattacks and thus cause more difficulties for the opponent (Mesquita et al., 2007). In addition, when a team recovers a ball, this increases the team’s motivation and often changes an unfavorable situation to a more positive one, encouraging the team to grow within the game. Therefore, Hypothesis 2, which posited that liberos would present the highest self-efficacy values due to their specific function within the court, was supported.

Dimension 3, Offensive Self-Efficacy in the Game, composed of items 1 (‘Assume the attack responsibility to decide the match’), Item 16 (‘Define a hard point’), and Item 17 (‘Be able to decide the match’), addresses offensive behaviors relevant to volleyball athletes. We observed in this dimension that the attackers (middle hitters, opposite hitters, and outside hitters) presented higher mean VSES scores, which was to be expected because of the particularity of their positions, with the attack being one of the main functions of these positions. For the liberos, this dimension presented a very low value, which shows that the offensive self-efficacy in this dimension is not helpful or necessary for evaluating players in this position.

The opposite hitter had the highest mean score, possibly due to their specialty of defining balls in the attack. With the constant updating of the rules of world volleyball, the characteristics of the player in this position have evolved with offensive functions in different zones of the court (Costa et al., 2016; Mesquita & César, 2007), playing a fundamental role in the offensive operations of highly competitive teams (Mesquita & César, 2007). Outside hitters, because of their many responsibilities, perform most of the functions in a match (e.g., attacking, passing, defending, serving), building the team’s tactical structure. The middle hitters’ role is more demanding concerning fast attacking and blocking functions, requiring a game reading of their team and the opposing team. They presented the lowest scores in this dimension, which can be understood due to the short time that middle hitters stay and remain in the defensive zone of the court. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 was also supported: Offensive Self-Efficacy in Volleyball would be the dimension in which the attackers (outside, middle, and opposite hitters) will obtain the highest self-efficacy values.

Regarding Global Self-Efficacy in Volleyball, the outside hitters presented the highest VSES scores, which was expected due to their role on the court, working with most of the game’s fundamentals and participating fully in the match. The liberos, on the other hand, had the lowest mean self-efficacy scores because they participated less in the game on the court, making exchanges with the middle hitter, most of the time, after the service and after the end of a rally or when the middle hitter makes a service error. Therefore, Hypothesis 4 was also verified: Global Self-Efficacy in Volleyball would be the dimension where outside hitters will obtain the highest mean scores.

This study has some limitations, including that the sample was obtained using non-probabilistic methods due to the total number of high-performance athletes registered in the competition and geographic logistics. Not all teams participating in the Superliga authorized their athletes to participate in the research.

Future investigations should compare self-efficacy between starting and reserve athletes and those of other collective sports, performance levels, countries, and languages. They should consider other variables, such as efficacy, effectiveness, collective efficacy, motivational climate, and group cohesion. Despite these limitations, the self-efficacy analysis according to positions played on the court, which has not previously been performed in studies of this sport, is an essential contribution to the understanding of this psychological construct in the context of high-performance volleyball, given that athletes at this level are subject to increasingly demanding training.

Final Considerations

The objective of this study was to analyze the self-efficacy of high-performance Brazilian volleyball athletes according to their positions. The efficacy beliefs regarding the position athletes play differed for all dimensions of the VSES, indicating specific behavioral qualities and expectations for the excellent performance of the offensive and defensive actions of the players for the performance of the modality. Regarding the Self-Efficacy in the Game dimension, the predominance of general aspects common to the self-efficacy of volleyball athletes as they relate to technical, tactical, and psychological elements inherent to the game was verified. Setters stood out in this dimension for their tactical intelligence, strategist function during matches, and high mean self-efficacy scores.

It should be emphasized that the liberos scored very low in the Offensive Self-Efficacy in Volleyball dimension, suggesting they used only two dimensions (Self-Efficacy in the Game and Defensive Self-Efficacy in Volleyball), in which they scored higher. Accordingly, we recommend using the mean of the two dimensions to determine the global self-efficacy of the liberos in Volleyball.

The outside hitters had the highest mean self-efficacy scores in the general context of the Global Self-Efficacy in Volleyball dimension because this position shares a little of each specialty with the other positions, making outside hitters the most complete player among the positions.

This study is expected to be helpful to all those involved in sports practice, whether they are researchers, coaches, physical trainers, sports psychologists, or other specialists. The study adds to the knowledge base concerning the preparation of athletes, who often know the particularities of their playing position. Based on these results, it is possible to work specifically on psychological skill training with athletes so that they can perform their functions on the court better, with improvements to or maintenance of their high self-efficacy, whether in training or in competitions, which further contributes to the promotion of their personal growth and development.