Serviços Personalizados

Journal

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Psicologia: teoria e prática

versão impressa ISSN 1516-3687

Psicol. teor. prat. vol.23 no.1 São Paulo jan./abr. 2021

https://doi.org/10.5935/1980-6906/ePTPC1913554

COVID-19

Parenting, mental health, and Covid-19: a rapid systematic review

Parentalidade, saúde mental e Covid-19: revisão sistemática rápida

Parentalidad, salud mental y Covid-19: una revisión sistemática rápida

Gabriela Vescovi ; Helena da S. Riter

; Helena da S. Riter ; Elisa C. Azevedo

; Elisa C. Azevedo ; Bruna G. Pedrotti

; Bruna G. Pedrotti ; Giana B. Frizzo

; Giana B. Frizzo

Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil

ABSTRACT

Parents face specific challenges during the pandemic and the period of social isolation since they need to cope with their children's demands besides their own. They are a key group to access and promote the wellbeing of children, especially in early development. This review systematically summarizes studies investigating the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic in parenting and parents' mental health. PRISMA guidelines were followed. We searched Google Scholar, PubMed, Scielo, Indexpsi, and PsycINFO databases. Ten articles met the criteria for the current literature review. The results showed significantly higher depressive and anxiety symptoms in parents/pregnant women than peers in a non-pandemic scenario. Parents and pregnant women's challenges were related to healthcare services during pregnancy, homeschooling, and loss of social support. This review provides relevant information to support tailored mental health interventions in response to Covid-19.

Keywords: Parenting; Mental health; Pandemic; Covid-19; Pregnancy; Social Isolation

RESUMO

Pais e mães enfrentam desafios específicos durante a pandemia e o período de isolamento social, pois precisam lidar com as demandas dos filhos além de suas próprias. Eles são um grupo chave para a promoção do bem-estar das crianças, especialmente no desenvolvimento inicial. Este artigo revisou sistematicamente estudos que investigaram os impactos da pandemia de Covid-19 na parentalidade e na saúde mental de pais e mães. As diretrizes PRISMA foram seguidas. As bases de dados Google Scholar, PubMed, Scielo, Indexpsi e PsycINFO foram acessadas. Dez artigos preencheram os critérios de inclusão. Os resultados mostraram uma frequência significativamente mais alta de sintomas depressivos e ansiosos em pais, mães e gestantes em comparação a pares em um cenário não-pandêmico. Os desafios enfrentados foram relacionados aos serviços de saúde durante a gravidez, às atividades escolares em casa e à perda de apoio social. Esta revisão fornece informações relevantes para apoiar intervenções de saúde mental em resposta ao Covid-19.

Palavras-chave: Parentalidade; saúde mental; pandemia; Covid-19; gestação; isolamento social.

RESUMEN

Padres y madres enfrentan desafíos específicos durante la pandemia y el período de aislamiento social, ya que necesitan lidiar con las demandas de sus hijos además de las propias. Son un grupo clave para acceder y promover el bienestar de los niños, especialmente en el desarrollo temprano. Esta revisión resumió sistemáticamente estudios que investigaron los impactos de la pandemia de Covid-19 en la parentalidad y la salud mental de padres y madres. Se siguieron las pautas de PRISMA. Se realizaron búsquedas en las bases de datos Google Scholar, PubMed, Scielo, Indexpsi y PsycINFO. Diez artículos cumplieron los criterios. Los resultados mostraron síntomas de depresión y ansiedad significativamente mayores en padres, madres y mujeres embarazadas en comparación con pares en un escenario no pandémico. Los desafíos que estos enfrentan están relacionados con los servicios de salud durante el embarazo, la educación en el hogar y la pérdida del apoyo social. Esta revisión proporciona información relevante para apoyar intervenciones de salud mental en respuesta a Covid-19.

Palabras clave: Cuidado parental; salud mental; pandemia; Covid-19; embarazo; Aislamiento social

1. Introduction

Covid-19 is a respiratory disease caused by the novel Coronavirus Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-Cov-2) and can cause mild to severe symptoms (World Health Organization [WHO], 2020a). Since its origin in December 2019, the virus has spread rapidly, turning into a pandemic. This situation has become a significant public health crisis, and its impact on mental health is a concern that increases each day (Holmes et al., 2020).

A pandemic situation can have relevant psychological effects such as stress, feelings of uncertainty, fear, and anxiety (Brooks, Weston, & Greenberg, 2020; Wang, Zhang, Zhao, Zhang, & Jiang, 2020). A study conducted in China, weeks after the epidemic began, identified moderate to severe depression and anxiety symptoms among the participants (Wang et al., 2020). The disease-related fears and social isolation, economic constraints, and abrupt changes in life and work routines pose an important burden on mental health (Ornell, Schuch, Sordi, & Kessler, 2020). Previous studies have shown that during epidemics, the number of people whose mental health is affected tends to be higher than the number of people affected by the infection (Shigemura, Ursano, Morganstein, Kurosawa, & Benedek, 2020).

Specific issues on parents' mental health have not been addressed in most scientific publications. It is plausible to consider that parents need to face particular challenges during this period of pandemic and social isolation since they need to cope with their children's demands besides their own. Disruptions in family organizations like working from home while conducting homeschooling, managing children's free time, and changes in children's behavior, in addition to the loss of social support, may present important challenges for families (Ministério da Saúde, 2020). As parents are relevant role models for children, good parenting skills become crucial when children are confined at home (Wang et al., 2020). Increased length of stay and contact within the household may leave parents overwhelmed and distressed, especially in crowded houses (Ministério da Saúde, 2020).

Parental stress can cause negative results for children's physical and mental health. Parent's mental health problems are associated with delays in child development (Kingston & Tough, 2014) and reduced quality in early interactions (Stein, Lehtonen, Harvey, Nicol-Harper, & Craske, 2009), which can have important implications for a child's socio-emotional and cognitive development. Consequently, parental mental health is a highly relevant construct that the Covid-19 pandemic may impact.

Some recommendations emphasize parents' role in managing children's emotions and behavior in the face of the pandemic, without considering parents' mental health as a factor interfering in these tasks (Wang et al., 2020). However, during such a crisis, being a parent increases the chances of stress. For instance, a study conducted during a disease epidemic in Australia identified that families with one child had 1.2 times higher risk of psychological distress than those with no children (Taylor, Agho, Stevens, & Raphael, 2008). Disease-containment measures, such as quarantine and isolation, can be traumatizing to a significant portion of children and parents. A study conducted in North America after the H1N1 outbreak (Sprang & Silman, 2013) found that 25% of confined or isolated parents met the criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder.

Pregnant women should also be paid attention to, as maternal mental health difficulties are related to adverse offspring developmental outcomes (Kingston & Tough, 2013). A systematic review of pregnant women's psychological needs during previous epidemics like SARS, Zika, and H1N1 (Brooks et al., 2020) found negative emotional states, especially anxiety, and an overestimated risk of being infected during pregnancy. They also highlighted that little attention had been paid to the potential psychological impact such outbreaks can have on pregnant women, regardless of their infection status.

Another source of distress during disasters is the decrease in healthcare access and quality. During the Ebola epidemic in Sierra Leone, fewer pregnant women accessed healthcare. For those who did, an increase in maternal mortality and stillbirth was observed (Jones, Gopalakrishnan, Ameh, White, & van den Broek, 2016). Additionally, restriction of visitors and mother-newborn separation are practices adopted in some countries in response to Covid-19 (Koons, 2020) that could have significant physical, psychological, and developmental effects for both women and infants.

It is an immediate priority to collect high-quality data on the mental health effects of the Covid-19 pandemic across the population and vulnerable groups (Holmes et al., 2020). We believe that parents are a key group to access and promote children's wellbeing, especially concerning early childhood development. Therefore, parents' mental health and parenting challenges in the current public health emergency are essential for designing interventions and public policies. For that reason, we conducted a systematic literature review about the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic on parenting and parents' mental health.

2. Method

We conducted a rapid systematic literature review in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Rapid reviews follow the general guidelines for traditional systematic reviews but are simplified to produce evidence rapidly; in this case, we did not conduct a quality appraisal of the included studies. When evidence synthesis is urgently needed, rapid reviews are recommended to inform public health guidelines and policies (WHO, 2017). We did follow the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines to systematically report the research literature (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009).

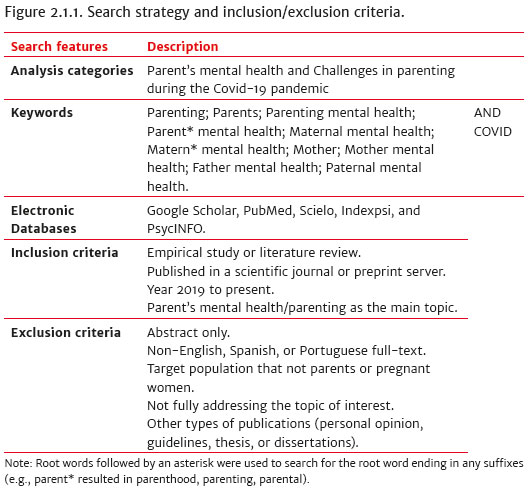

2. 1 Search strategy

The search strategy is described in Figure 2.1.1. According to our objective, two categories were previously defined: parents' mental health and parenting challenges during the current pandemic. Keywords were then selected to encompass these themes and were searched in combination with "COVID" by utilizing the Boolean operator "and" at Google Scholar (GS), PubMed, Scielo, Indexpsi, and PsycINFO databases. In the GS database, due to its high sensitivity (Gehanno, Rollin, & Darmoni, 2013), we used quotation marks in each keyword to narrow the results to our topic of interest. As those authors suggested, to improve GS precision, advanced search features were used: in the searches with over one thousand results, we used the filter "all in title." That resulted in specific documents related to the topic of interest, increasing precision successfully and apparently without any critical loss.

2. 2 Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria for eligible documents included an empirical or literature review study published in a scientific journal or preprint server (such as medRxiv and PsyArxiv) between 2019 and 2020. The articles must have addressed the topic (parenting and parents' mental health during Covid-19) as the main issue. Due to the rapid need for publication since the pandemic started, we did not consider peer-review as an inclusion criterion.

3. Results

3.1 Search results

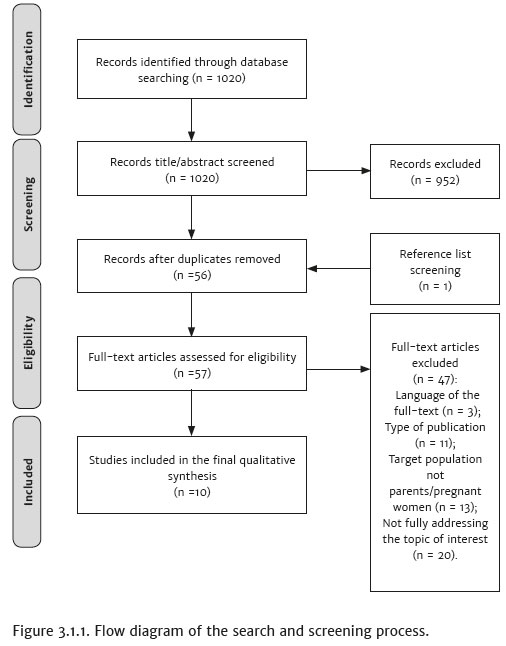

The searches were conducted between April 24 and 29, 2020. The PRISMA diagram describes the search and screening process (Figure 3.1.1). A total of 1020 documents were initially retrieved from the databases (Pubmed = 88; GS = 932). Throughout reading the titles and abstracts, 912 documents were excluded. The remaining 68 files were then checked for duplicates, resulting in 56 articles. We screened the reference lists of those 56 studies, resulting in one additional study included. A total of 57 full-text documents were then eligible. At least two authors screened each study. Disagreements were resolved through group discussion.

Forty-seven articles were further excluded due to: the language of the full-text (n = 3); type of publication (n = 11), including opinion and institutional guidelines; target population that was not parents/pregnant women (n = 13), such as the general adult population or children; and not fully addressing the topic of interest (n = 20). This last criterion was intended for articles that addressed some of the subjects of interest (parents/pregnant women, mental health/parenting, and Covid-19), but not all of them and not with the focus established in this review (impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic on mental health and/or parenting). Therefore, studies were excluded because of their focus on physical health (pregnancy or birth outcomes related to Covid-19), health education for parents (suggested activities to do with children during quarantine, how to deal with children's emotions), violence, or because they did not include Covid-19.

Ten research articles were found to meet the criteria for the current literature review after assessing eligibility. A deductive thematic analysis (Braun, Clarke, Heyfield, & Terry, 2019) was conducted using Nvivo 12 software. The two categories previously defined (Figure 2.1.1) were created as nodes in Nvivo, and excerpts of texts from the articles were allocated to each node. The first author reviewed this process.

Included studies

At the time of the search, most of the included articles were shared in preprint servers (n = 6). The ones published in scientific journals included psychiatry or medical journals. Nine studies were published in English, one in Spanish and none in Portuguese. As for the study design, seven articles were quantitative, one was qualitative, and two conducted literature reviews. Among the empirical studies (n = 8), research was conducted in China (n = 4), the UK (n = 2), the Czech Republic (n = 1), and Canada (n = 1). Figure 3.1.2 provides a methodological overview of the ten included studies. Regarding the target population, five studies investigated parents, and three inquired pregnant women. Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) was used in two articles. Due to distancing measures, five studies appealed to online surveys. Only one study conducted an intervention (Huang et al., 2020).

Results of the included studies will be presented concerning (a) Parent's mental health and (b) Challenges in parenting during the pandemic.

3. 2 Parent's mental health

Eight studies addressed parents' mental health. They either investigated mental health as a broad concept (Asbury, Fox, Deniz, Code, & Toseeb, 2020; Bai, Wang, Liang, Qi, & He, in press; Topalidou, Thomson, & Downe, 2020), measured depression and anxiety symptoms (Huang et al., 2020; Lebel, MacKinnon, Bagshawe, Tomfohr-Madsen, & Giesbrecht, 2020; Wu et al., 2020, Yuan et al., 2020), or described possible interventions on national or individual levels (Bermejo-Sánchez, Peña-Ayudante, & Espinoza-Portilla, 2020; Huang et al., 2020). The results showed significantly higher depressive and anxiety symptoms in parents/pregnant women than peers in a non-pandemic scenario (Wu et al., 2020; Yuan et al., 2020). An alarming finding was made by Wu and colleagues (2020) regarding higher scores for thoughts of self-harm (p = 0.005) in the post-pandemic group of pregnant women in China. Lebel et al. (2020) reported a prevalence of 37% of clinically elevated symptoms of depression (EPDS scores >13) among Canadian pregnant women, as well as 56.6% of clinically elevated anxiety. Compared with previous (before the pandemic) community pregnancy cohorts with similar demographic profiles, the authors concluded that their results were all substantially higher.

None of the studies directly compared parents/pregnant women with the general adult population (non-parents) during the pandemic to evaluate if the mental health impact of Covid-19 was different. However, Lebel et al. (2020) did compare their findings with another prevalence study in the general population exposed to Covid-19. They found that the rates of clinically relevant symptoms in their pregnancy cohort were higher, suggesting that the outbreak's psychological impact may be of particular concern for pregnant individuals.

Parents with an increased probability of worse mental health scores during the Covid-19 pandemic were women living in cities and parenting children under three years old (Bai et al., 2020). Interestingly, pregnant women with low-risk factors for depression in normal situations (like full-time work, primiparous, middle-income level, adequate living area, and younger maternal age) became vulnerable to perinatal depression after the outbreak (Wu et al., 2020). The odds of clinically elevated depression symptoms among pregnant were increased by low social support (Lebel et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020) and by Covid-19-related worries (Lebel et al., 2020) and awareness (Wu et al., 2020). Covid-19-related concerns and parents' concerns about their children were also strongly correlated with parents' worse mental health scores (Bai et al., 2020).

Two studies found that first-time pregnant women had higher pregnancy-related anxiety rates (Lebel et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020). Primiparas and younger mothers tended to have more intense psychological responses to an infection outbreak, perhaps because of less experience coping with pregnancy- and baby-related stress (Wu et al., 2020). The most significant effect observed in pregnancy-related anxiety was not getting the prenatal care needed (Lebel et al., 2020), a topic that will be addressed in the next section. Contrarily, protective factors identified for pregnant women's mental health were better social support levels and longer sleep duration (Lebel et al., 2020).

Included research also investigated parents' feelings. Pregnant women reported feeling more alone than usual due to the pandemic, corresponding to 92% of Lebel et al.'s (2020) sample. One study (Asbury et al., 2020) reported feelings of worry, fear, stress, and anxiety among parents of children with Special Education Needs and Disabilities (SEND). While low mood and distress are likely to be widespread during the pandemic, the authors suggested they may be experienced more severely within the SEND community.

This new scenario, imposed by the Covid-19 pandemic and distancing measures, calls for innovative parents' mental health interventions. Bermejo-Sánchez et al. (2020) suggested using technologies and social media to prevent and intervene in perinatal depression through artificial intelligence tools, mental health hotlines and online counseling, and virtual assistance (like chatbots), and online peer-support provided by volunteer women that experienced perinatal depression in the past. These may be relevant actions taken by governments to address perinatal depression during and after the pandemic since social distancing measures will most probably endure.

Huang et al. (2020) described the successful use of a three-session Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT)-based psychological intervention in improving anxiety and depressive symptoms in a hospitalized pregnant woman with Covid-19. At the third session, the patient was able to control her emotions, express her feelings, and obtain support. Although these two reported interventions are not restricted to parents, the studies point out the need to consider this population's particularities.

Topalidou et al. (2020) conducted a rapid evidence review before April 6, 2020, and they did not find any studies relating Covid-19 to maternal mental health. The authors stated that there is a critically important gap in our knowledge about how pandemics affect mothers and their babies and how these families can be better supported, a gap that the current review is trying to, at least partially, address. Only two of the included studies (Brom et al., 2020; Toseeb, Asbury, Code, Fox, & Deniz, in press) did not directly investigate parents' mental health but addressed parenting challenges discussed next.

3. 3 Challenges in parenting during the pandemic

Six studies reported challenges that parents and pregnant women may face during the pandemic. These challenges were related to healthcare services during pregnancy (Lebel et al., 2020; Topalidou et al., 2020), homeschooling (Brom et al., 2020; Toseeb et al., in press), and loss of social support (Asbury et al., 2020; Brom et al., 2020; Lebel et al., 2020; Toseeb et al., in press; Wu et al., 2020).

During a pandemic, access to healthcare services and prenatal care can be a challenge for pregnant women. Lebel et al. (2020) found that most participants (89%) needed to make prenatal care changes due to the pandemic, including canceled appointments and alterations in their birth plan. Most women (82,4%) believed that their prenatal care quality had decreased, and 74% of the sample had trouble accessing other healthcare services during their pregnancy (massage therapy services, chiropractic, and psychological counseling). Notably, 90% were not allowed to bring a support person during prenatal care.

Another challenge experienced in health services was the mother-newborn separation policy. The potential (ill-informed) practices of separating mothers from their infants post-birth, in the name of protection from Covid-19 infection, such as witnessed in Huang et al.'s (2020) Chinese study, for instance, can have harmful impacts on maternal mental health via toxic stress (Topalidou et al., 2020). The authors stated that policies to restrict maternal choices in the name of protection of the mother and baby are not justified based on current evidence and are likely to be associated with longer-term harm, both physical and psychological (Topalidou et al., 2020).

Regarding the challenge of homeschooling during the pandemic, some parents of children with SEND felt that their children did not have sufficient support after schools were closed and that they had been asked to do a challenging job without any training (Toseeb et al., in press). On the other hand, Brom et al. (2020) found that Czech families coped well with helping their children with classes and homework, but some parents reported difficulties. They mentioned a lack of time, as most parents helped their children around two hours a day, which competed with other essential tasks. Besides, most parents believed that the amount of schoolwork was too much. Parents of older children reported a higher perception that time was too short for a large number of tasks (Brom et al., 2020).

Parents also cited the limited number of technological devices as a difficulty since they needed the same devices to work. Finally, the lack of expertise was also pointed out as a challenge. Parents believed they did not know the subjects or didactics to motivate their children. When asked what would help the most, parents mentioned smaller amounts of assigned tasks, a more direct teacher's presence during homeschooling, and more interactivity between children and teachers (Brom et al., 2020).

The loss of social support emerged as a critical challenge during the outbreak. It was mentioned as a difficulty by parents handling homeschooling (Brom et al., 2020) and parents of children with SEND (Asbury et al., 2020; Toseeb et al., in press). Also, the prohibition of a support person was a barrier to quality prenatal care (Lebel et al., 2020). As referred earlier, low social support was associated with worse mental health outcomes (Lebel et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020). The disruptive effects of social isolation on the routine were observed on parents of children with SEND (Asbury et al., 2020; Toseeb et al., in press). Some single parents are isolated with a child who displays very challenging behavior without access to any support or respite. Such stressors can influence the quality of family relationships, making empathic parenting difficult. These parents would like to have specialist professional advice or help to implement a new routine, keeping in mind their child's special educational needs and disabilities, like appropriate educational activities (Toseeb et al., in press).

4. Discussion

The present review suggests that Covid-19 has an important impact on parents' mental health. As will be discussed next, regarding parents, not only Covid-19-related preoccupations but mostly the loss of social support caused by distancing measures may be a burden for parents' mental health when managing disruptions in routine, mainly homeschooling, especially in cases of children with SEND. Besides, included studies also indicate high levels of anxiety and depression among pregnant women, mainly due to reduced social support and difficulties accessing prenatal care.

Results of the included studies indicate a high prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms among pregnant women and parents. During disaster situations, mental health problems such as postpartum depression, psychosis, and post-traumatic stress disorder are more frequent (Sprang & Silman, 2013). This higher frequency was observed in the present review when studies compared pre- and post-pandemic cohorts. Covid-related worries, parents' concerns with their children, and an increasing number of deaths per day were all related to parents' mental health issues according to included studies. In the same direction, a qualitative study conducted with Chinese parents after the SARS outbreak in Hong Kong pointed out that most parents expressed worry about their young children and became more fearful when the death toll increased (Wong, Chan, Tang, & Lam, 2007).

While this manuscript was being written, the American Psychological Association (2020) released preliminary results in the US, showing significantly higher stress-related rates to Covid-19 in parents compared with the adult population without children. 71% of these parents identified managing distance/online learning for their children as a significant source of stress aligned with the current review results. Also, parents were more likely than those without children to say basic needs (such as food and housing), and access to healthcare services were significant sources of stress (American Psychological Association, 2020). These results support our initial idea that parents have increased preoccupations during emergency events, even though more comparative research is needed.

This mental health burden on parents should be a concern since they are, during quarantine, the only support system for children. Caregiver preoccupation may act as a proximal step in transmitting psychiatric disturbance to the offspring, interfering with the parents' capacity to attend to their infants and provide responsive interactions (Stein et al., 2009). Additionally, stressful home environments for children, especially those with maternal mental health problems and harsh parenting styles, are related to children's difficulties in socio-emotional skills (Moroni, Nicoletti, & Tominey, 2020) and delays in development (Kingston & Tough, 2014).

Social support emerged as a relevant factor for parents during the Covid-19 crisis. The loss of support networks because of distancing measures was associated with worse mental health outcomes (Lebel et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020) and was mentioned as a challenge for parenting (Asbury et al., 2020; Brom et al., 2020; Lebel et al., 2020; Toseeb et al., in press; Wu et al., 2020). On the other hand, social support was identified as a protective factor for pregnant women (Lebel et al., 2020).

Once it is known that having a social support network acts as a protective factor for pre- and postnatal depressive symptoms (Maffei, Menezes, & Crepaldi, 2019), it is important to consider the negative effects of social isolation on pregnant women's mental health. A study conducted in the US (Brock et al., 2014) showed that social support might effectively mitigate the link between prenatal disaster stress and maternal depression when it is informational (advice), instrumental (help), or emotional (communication of confidence to handle a problem). The frequency of received physical comfort did not interact with prenatal disaster stress.

These findings indicate that even with distancing measures, it is still possible to provide adequate support for parents and pregnant women to protect them from mental health issues precipitated by the pandemic. By suggesting that technologies and social media can be a source of support for pregnant and postpartum women during the lockdown, Bermejo-Sánchez et al. (2020) are aligned with these results, providing relevant and evidence-based interventions for governments to consider when implementing public mental health policies during and after this crisis.

Even with the loss of support, parents need to deal with the age-specific demands of their children. According to Bai et al. (2020), caring for children under three years old in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic was related to worse mental health scores on parents. Later in the development cycle, even school-age children and adolescents, who already have more autonomy, need assistance, especially with homeschooling (Brom et al., 2020; Toseeb et al., in press). Although some countries like China, Vietnam, and the UK tried to support parents in homeschooling tasks through television broadcasts (Moroni et al., 2020), this is not a reality for most parents (and there's still no research on parents' satisfaction with this practice). The difficulties regarding homeschooling may be expanded by the loss of support networks, such as other family members and daycare centers, overlapped with parents working from home and domestic tasks (Alon, Doepke, Olmstead-Rumsey, & Tertilt, 2020; Ornell et al., 2020). The absence of support may create a more substantial burden than in just one specific stage of children's development, although more research is needed to support this hypothesis.

Lack of social support is related to parental burnout, a syndrome in reaction to parental stress (Gérain & Zech, 2018). As mentioned earlier, the current scenario, with infection-related concerns and accumulation of work and household tasks, seems propitious to developing depression, anxiety, and stress among parents. Those caring for children with special needs are also at increased risk of developing burnout (Gérain & Zech, 2018). The current review suggests that an infectious-disease outbreak can intensify the pressure to handle all the demands that a SEND child needs (Asbury et al., 2020; Toseeb et al., in press). Additionally, the lack of social support in the Covid-19 context can be even harder for these parents to experience, making them especially vulnerable to mental health suffering.

There is no sufficient evidence to determine if pregnant, birthing, postpartum, and lactating women are at an increased risk of Covid-19 infection or severe cases (WHO, 2020b). Still, they are a unique population that needs to be targeted for mental health research and intervention during emergencies and disasters (Holmes et al., 2020). Past crises, such as the Ebola outbreak, have taught us that pregnant women affected by these situations do not receive appropriate prenatal and birth care, increasing psychological distress and adverse birth outcomes (Jones et al., 2016). The present review suggests this may also be true during the Covid-19 pandemic, even in high-income countries, since pregnant women reported decreased prenatal care quality. For instance, that explains the rising rates of maternal mortality, especially among black and Latino communities in the US (Raman, 2020), amplifying racial disparities. Besides that, the mother-newborn separation policy adopted in some countries poses additional stress for women and infants and is not recommended by the World Health Organization (2020b).

The impacts of Covid-19 seem to hit women and men differently. Data found in the current review suggest that the Covid-19 pandemic may further extend the already existing global gender inequality in parenting (United Nations Development Programme [UNDP], 2020). Traditionally, women are the ones who take on the role of informal care within families (Alon et al., 2020) and will probably be responsible for childcare and homeschooling with little or no social support network, as shown in the present review. The role of women as the primary caregiver can be evidenced by considering who participated in the research about their kids: among the five included studies that investigated parents, in four of them, the majority of the sample (over 70%) were mothers (Figure 3.1.2).

The results from Bai et al. (2020) also indicate that urban-living mothers in China are at increased risk of poor mental health outcomes compared with fathers, probably because they accumulate childcare and work activities. Working and single moms may be exposed to an even bigger load, increasing the work-related gender gap (Alon et al., 2020). An example is shown in a preliminary report in Brazil, which found a decrease in the number of scientific papers authored by women than men since the pandemic started (Candido & Campos, 2020). This gender-oriented impact of the pandemic is relevant not only to women's mental health but also to the next generation since parenting practices and behaviors are among the predictors of an individual's gendered behaviors and expectations (UNDP, 2020).

It is relevant to consider that the studies found in the current review were carried out mostly in high-income countries. Besides, online data collection used in most empirical studies can lead to sample bias, with respondents not being representative of the whole population, especially in terms of socioeconomic status and ethnic diversity (Hunter, 2012). Brom et al. (2020) mentioned the difficulty of accessing families of low socioeconomic level via an online survey and the fact that these groups' experiences may be even more invisible in a period of social isolation in which face-to-face interviews are not possible. Moreover, the economic difficulty is associated with higher parental stress levels and mental health problems of caregivers and their children (Newland, Crnic, Cox, & Mills-Koonce, 2013). Wu et al. (2020) also point in this direction since their results showed that social and family conditions, such as low annual family income and lower level of education, increased the risk of perinatal depression, besides the effect of Covid-19. Therefore, the results found in this review should be cautiously taken into account when considering more vulnerable contexts.

Still, low-income families' financial instability may put them at higher risk of suffering the economic impacts caused by Covid-19. Bai et al. (2020) found that pandemic impacted most families' income (77%). However, parents reported that it did not affect their quality of life. In this way, it is possible to consider that the medium- and high-income accessed families have more means to guarantee the quality of life, despite the decrease in revenue. That might not be true in low- and middle-income countries. Holmes et al. (2020) consider that low-income families experience the Covid-19 pandemic differently due to professional and financial instability, cramped housing, and restricted access to technology. They suggest that mental health effects are different in this group and need to be studied in-depth and prioritized in interventions. Thus, it is plausible that these families are even more vulnerable to the pandemic social and health effects and need more government support. However, they may be the most invisible population in research.

Even though we did not conduct a systematic appraisal of the included studies, it is clear that they reflect a very initial research body (cross-sectional studies and case reports, for example). On the other hand, most studies inquired about a relevant number of participants, which was only possible throughout an online assessment. As mentioned, this method has its disadvantages (Hunter, 2012), yet it is an essential alternative in times of mandatory social distancing. The current public health emergency state compels researchers to produce evidence fast, which sometimes reduces methodological quality. It is worth noting that some of the included studies did not use internationally-recognized instruments to assess mental health (Asbury et al., 2020; Bai et al., 2020) or social support (Toseeb et al., in press; Wu et al., 2020) and for that reason need to be interpreted with caution. Nevertheless, we believe that the current review accomplishes its goal by providing important aspects that should be considered when addressing parents' mental health during and after the Covid-19 outbreak.

The present study aimed to systematically review research about the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic in parenting and parents' mental health. Our results suggest that the current outbreak has relevant mental health impacts on parents and pregnant women. Social support's loss seemed to be a key element in the mental health burden observed in parents. This review provides relevant information to support tailored mental health interventions in response to Covid-19. Pregnant women, single working mothers, parents of children with disabilities, and low-income families all require government attention. Additionally, homeschooling policies need to consider parents' mental health since overwhelmed parents may not properly conduct educational tasks for children.

The current review has some limitations. As scientific knowledge is growing fast during the pandemic, this review reflects the studies available at the moment searches were conducted. We did not systematically evaluate the methodological quality of the included studies. For that reason, results should be interpreted with caution. On the other hand, all the evidence seems to point in the same direction.

Epidemiological studies should investigate the population's parental status more frequently since this variable seems to be related to mental health outcomes, especially during public health emergencies such as Covid-19. Future research should also address parents' social support as it emerged as a relevant aspect of this population besides mental health scores alone. Additionally, researchers need to tackle online data collection specifics to adapt to new distancing and sanitary measures during and after the Covid-19 pandemic, especially to include more vulnerable populations.

References

Alon, T. M., Doepke, M., Olmstead-Rumsey, J., & Tertilt, M. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on gender equality. National Bureau of Economic Research. doi:10.3386/w26947 [ Links ]

American Psychological Association (2020). APA Stress in America report: High stress related to Coronavirus is the new normal for many parents. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2020/05/stress-america-covid-19?utm_source=facebook&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=apa-press-release-sia2020&utm_content=sia-covid19-pt1-may21&fbclid=IwAR0cwIhV4LOMmIvE7BkrJlGTaV4j6zmFIwkGvOrpyDDkQIqwHCFV-9_begs [ Links ]

Asbury, K., Fox, L., Deniz, E., Code, A., & Toseeb, U. (2020). How is COVID-19 affecting the mental health of children with special educational needs and disabilities and their families? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. doi:10.31234/osf.io/sevyd [ Links ]

Bai, R., Wang, Z., Liang, J., Qi, J., & He, X. (in press). The effect of the COVID-19 outbreak on children's behavior and parents' mental health in China: A research study. Research Square, 1-21. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-22686/v1 [ Links ]

Bermejo-Sánchez, F. R., Peña-Ayudante, W. R., & Espinoza-Portilla, E. (2020). Depresión perinatal en tiempos del COVID-19: Rol de las redes sociales en Internet. Acta Médica Peruana, 37(1). doi:10.35663/amp.2020.371.913 [ Links ]

Braun, V., Clarke, V., Hayfield, N., & Terry, G. (2019). Thematic Analysis. Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences, 843-860. [ Links ]

Brock, R. L., O'Hara, M. W., Hart, K. J., McCabe, J. E., Williamson, J. A., Laplante, D. P., ... King, S. (2014). Partner support and maternal depression in the context of the Iowa floods. Journal of Family Psychology, 28(6),832-843. doi:10.1037/fam0000027 [ Links ]

Brom C., Lukavský J., Greger, D., Hannemann, T., Straková, J., & Švaříček, R. (2020). Mandatory Home Education During the COVID-19 Lockdown in the Czech Republic: A Rapid Survey of 1st-9th Graders' Parents. Frontiers in Education, 5,103. doi:10.3389/feduc.2020.00103

Brooks, S. K., Weston, D., & Greenberg, N. (2020). Psychological impact of infectious disease outbreaks on pregnant women: Rapid evidence review. Public Health, 189, 26-36. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2020.09.006 [ Links ]

Candido, M. R., & Campos, L. A. (2020, May 14). Pandemia reduz submissões de artigos acadêmicos assinados por mulheres. Dados - Revista de Ciências Sociais. Retrieved from http://dados.iesp.uerj.br/pandemia-reduz-submissoes-de-mulheres/ [ Links ]

Gehanno, J., Rollin, L., & Darmoni, S. (2013). Is the coverage of google scholar enough to be used alone for systematic reviews? BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 13(7). doi:10.1186/1472-6947-13-7 [ Links ]

Gérain, P., & Zech, E. (2018). Does informal caregiving lead to parental burnout? Comparing parents having (or not) children with mental and physical issues. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00884 [ Links ]

Holmes, E. A., O'Connor, R. C., Perry, V. H., Tracey, I., Wessely, S., Arseneault, L., ... Bullmore, E. (2020). Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry, 7,547-560. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1 [ Links ]

Huang, J., Zhou, X., Lu, S., Xu, Y., Hu, J., Huang, M., ... Wei, N. (2020). Dialectical behavior therapy-based psychological intervention for woman in late pregnancy and early postpartum suffering from COVID-19: A case report. Journal of Zhejiang University-SCIENCE B, 21(5),394-399. doi:10.1631/jzus.B2010012 [ Links ]

Hunter, L. (2012). Challenging the reported disadvantages of e-questionnaires and addressing methodological issues of online data collection. Nurse Researcher, 20(1),11-20. doi:10.7748/nr2012.09.20.1.11.c9303 [ Links ]

Jones, S. A., Gopalakrishnan, S., Ameh, C. A. White, S., & van den Broek, N. R. (2016). 'Women and babies are dying but not of Ebola': The effect of the Ebola virus epidemic on the availability, uptake, and outcomes of maternal and newborn health services in Sierra Leone. BMJ Global Health, 1(3). doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000065 [ Links ]

Kingston, D., & Tough, S. (2014). Prenatal and postnatal maternal mental health and school-age child development: A systematic review. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 18(7),1728-1741. doi:10.1007/s10995-013-1418-3 [ Links ]

Koons, C. (2020, March 24). No hand to hold: Women face labor alone at slammed NYC hospitals. Bloomberg. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-24/hospitals-in-nyc-are-forcing-women-to-give-birth-alone-amid-covid [ Links ]

Lebel, C., MacKinnon, A., Bagshawe, M., Tomfohr-Madsen, L., & Giesbrecht, G. (2020). Elevated depression and anxiety symptoms among pregnant individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of affective disorders, 277,5-13. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.126 [ Links ]

Maffei, B., Menezes, M., & Crepaldi, M. A. (2019). Significant social network in the gestational process: An integrative review. Revista da SBPH, 22(1),216-237.Retrieved from http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1516-08582019000100012&lng=pt&tlng=pt [ Links ]

Ministério da Saúde (2020). Crianças na pandemia COVID-19. Saúde mental e atenção psicossocial na pandemia COVID-19. Retrieved from https://www.fiocruzbrasilia.fiocruz.br/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/crianc%cc%a7as_pandemia.pdf [ Links ]

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & Altman, D. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7),e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [ Links ]

Moroni, G., Nicoletti, C., Tominey, E. (2020, April 9). Children's socio-emotional skills and the home environment during the COVID-19 crisis. VoxEU. Retrieved from https://voxeu.org/article/children-s-socio-emotional-skills-and-home-environment- during-covid-19-crisis [ Links ]

Newland, R. P., Crnic, K. A., Cox, M. J., & Mills-Koonce, W. R. (2013). The family model stress and maternal psychological symptoms: Mediated pathways from economic hardship to parenting. Journal of Family Psychology, 27(1),96-105. doi:10.1037/a0031112 [ Links ]

Ornell, F., Schuch, J. B., Sordi, A. O., & Kessler, F. (2020). "Pandemic fear" and COVID-19: Mental health burden and strategies. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry, 42(3),232-235, doi:10.1590/1516-4446-2020-0008 [ Links ]

Raman, S. (2020, May 14). COVID-19 amplifies racial disparities in maternal health. Roll Call. Retrieved from https://www.rollcall.com/2020/05/14/covid-19-amplifies-racial-disparities-in-maternal-health/ [ Links ]

Shigemura, J., Ursano, R. J., Morganstein, J. C., Kurosawa, M., & Benedek, D. M. (2020). Public responses to the novel 2019 coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Japan: Mental health consequences and target populations. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 74,281-282. doi:10.1111/pcn.12988 [ Links ]

Sprang, G., & Silman, M. (2013). Posttraumatic stress disorder in parents and youth after health-related disasters. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 7(1),105-110. doi:10.1017/dmp.2013.22 [ Links ]

Stein, A., Lehtonen, A., Harvey, A. G., Nicol-Harper, R., & Craske, M. (2009). The influence of postnatal psychiatric disorder on child development: Is maternal preoccupation one of the key underlying processes? Psychopathology, 42(1),11-21. doi:10.1159/000173699 [ Links ]

Taylor, M. R., Agho, K. E., Stevens, G. J., & Raphael, B. (2008). Factors influencing psychological distress during a disease epidemic: Data from Australia's first outbreak equine influenza. BMC Public Health, 8(347). doi:10.1186/1471-2458-8-347 [ Links ]

Topalidou, A., Thomson, G., & Downe, S. (2020). Covid-19 and maternal and infant health: Are we getting the balance right? A rapid scoping review. The Practising Midwife, 23(7). Retrieved from https://www.all4maternity.com/covid-19-and-maternal-and-infant-health-are-we-getting-the-balance-right-a-rapid-scoping-review/ [ Links ]

Toseeb, U., Asbury, K., Code, A., Fox, L., & Deniz, E. (in press). Supporting families with children with special educational needs and disabilities during COVID-19. PsyArXiv Preprints. doi:10.31234/osf.io/tm69k [ Links ]

United Nations Development Programme (2020). Tackling social norms: A game changer for gender inequalities. 2020 Human Development Perspectives. Retrieved from http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/hd_perspectives_gsni.pdf [ Links ]

Wang, G., Zhang, Y., Zhao, J., Zhang, J., & Jiang, F. (2020). Mitigate the effects of home confinement on children during the COVID-19 outbreak. The Lancet, 395,945-947. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30520-1 [ Links ]

Wong, W. C. W., Chan, K., Tang, H., & Lam, M.W. L. (2007). The cycle fear: A qualitative study of SARS and its impacts on kindergarten parents one year after the outbreak. The Hong Kong Practitioner, 29(4),146-155. Retrieved from http://www.hkcfp.org.hk/Upload/HK_Practitioner/2007/hkp2007vol29apr/original_article_3.html [ Links ]

World Health Organization (2017). Rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems: A practical guide. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/alliance-hpsr/resources/publications/rapid-review-guide/en/ [ Links ]

World Health Organization (2020a). Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/ 30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov) [ Links ]

World Health Organization (2020b). Q&A on COVID-19, pregnancy, and childbirth. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/question-and-answers-hub/q-a-detail/q-a-on-covid-19-pregnancy-and-childbirth [ Links ]

Wu, Y., Zhang, C., Liu, H., Duan, C., Li, C., Jianxia Fan, J., ... Huang, H. (2020). Perinatal depressive and anxiety symptoms of pregnant women during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in China. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 223(2),240.e1-240.e9. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7211756/pdf/main.pdf [ Links ]

Yuan, R., Xu, Q.-H., Xia, C.-C., Lou, C.-Y., Xie, Z., Ge, Q.-M., & Shao, Y. (2020). Psychological status of parents of hospitalized children during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Psychiatry Research, 288,112953. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112953 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Gabriela Vescovi

Rua Ramiro Barcelos, 2600, sala 212, Bairro Santa Cecília

Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil. CEP 90035-003

E-mail: gabriela.vescovi@gmail.com

Submission: 29/06/2020

Acceptance: 30/10/2020

The authors thank CAPES and CNPq for the scholarships to the postgraduation students.

Author's notes

Gabriela Vescovi, Postgraduate Program in Psychology (PPG Psicologia), Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS); Helena da S. Riter, Postgraduate Program in Psychology (PPG Psicologia), Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS); Elisa C. Azevedo, Postgraduate Program in Psychology (PPG Psicologia), Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS); Bruna G. Pedrotti, Postgraduate Program in Psychology (PPG Psicologia), Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS); Giana B. Frizzo, Postgraduate Program in Psychology (PPG Psicologia), Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS).