Serviços Personalizados

artigo

Indicadores

Compartilhar

Temas em Psicologia

versão impressa ISSN 1413-389X

Temas psicol. vol.26 no.4 Ribeirão Preto out./dez. 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.9788/TP2018.4-16Pt

ARTICLE

Socioeconomic level and self-perception as a romantic partner in a university setting

Anthonieta Looman MafraI; Felipe Nalon CastroII; Fívia de Araújo LopesIII

IOrcid.org/0000-0002-7612-8778. Universidade Potiguar - Laureate International Universities, Natal, RN, Brasil

IIOrcid.org/0000-0002-6690-5182. Universidade Potiguar - Laureate International Universities, Natal, RN, Brasil

IIIOrcid.org/0000-0002-8388-9786. Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, RN, Brasil

ABSTRACT

From an Evolutionary Psychology perspective, men and women exhibit different sexual preferences. These preferences are modulated by the self-perception of individuals, which may also be affected by context. The present study sought to determine whether economic context, as indicated by purchasing power, affects self-perception as a romantic partner. To that end, 316 university students completed a questionnaire containing questions on socioeconomic status and self-perception as a romantic partner. The results indicated that self-perceived financial situation differed according to socioeconomic level. However, the difference in perceived general attractiveness was higher in class A men than in women from the same economic class, while for the determined/hardworking trait, there was a difference between sexes, in which women perceived that they were better than men. The results support the theory of strategic pluralism, showing that the environment can influence the partner selection process by increasing the general attractiveness perceived by men in the highest economic class (A) compared to the other groups in the sample. Moreover, the results suggest inequality between the sexes in terms of self-perception as a romantic partner.

Keywords: Self-perception, Evolutionary Psychology, university students, socioeconomic level, human reproduction.

The sexual strategies theory predicts that males and females tend to select their mates with a view to maximizing reproductive success (Buss & Schmitt, 1993). It is no diffe-rent in humans. According to the same authors, individuals who exhibit preferences for partners with traits indicating genes favorable to the transmission of desirable characteristics are likely have greater reproductive success than those who do not. In accordance with the evolutionary perspective, this is one of the reasons that gave rise to male and female behavioral patterns in the search for romantic partners (Gaulin & McBurney, 2001).

Given that physical attractiveness provides important clues about physical condition and women's overall reproductive health (which may explain the high physiological investment in offspring), men demonstrate greater interest in women considered more physically attractive (Buss, 1989; Castro, Hattori, Yamamoto, & Lopes, 2013; Geary, Vigil, & Byrd-Craven, 2004; Gutierres, Kenrick, & Partch, 1999; Kenrick, Sadalla, Groth, & Trost, 1990; Kruger, Fitzgerald, & Peterson, 2010; Pawlowski, 2000). However, women are not alone in investing in children. Despite their low physiological investment, men may provide care, protection and resources for their partner and children (Buss, 1989; Castro & Lopes, 2011; Geary et al., 2004; Hattori, Castro, & Lopes, 2013; Pawlowski, 2000). In this respect, traits related to social status tend to stand out in female preferences when compared to men's (Buss, 1989; Castro & Lopes, 2011; Castro et al., 2013; Gaulin & McBurney, 2001; Geary et al., 2004; Hattori et al., 2013; Pawlowski, 2000). However, some characteristics are equally important to men and women when seeking a partner (Castro & Lopes, 2011; Hattori et al., 2013; Mafra & Lopes, 2014). One example is faithfulness, which is highly valued by men and women, because it guarantees the former's paternity (Dosmukhambetova & Manstead, 2011; Trivers, 1972) as well as men's investment in their partner and offspring (Gaulin & McBurney, 2001).

In addition to the search for satisfaction in preferences, researchers contend that for a relationship to last a partner with similar market value (reproductive value of an individual in a particular environment) should be selected (Buston & Emlen, 2003; Castro, Hattori, & Lopes, 2012; Lee, Loewenstein, Ariely, Hong, & Young, 2008). As such, both the productive value of potential partners and self-perception must be assessed. The self-perceived value of an individual's attributes in a given context is affected by the comparison with the perceived value of competitors (Castro et al., 2012; Fisher, Cox, Bennett, & Gavric, 2008; Pawlowski, 2000).

Buston and Emlen (2003), in a study with American university students, confirmed that individuals who have better self-assessment are more demanding than those with lower self-assessment when seeking a romantic partner, which indicates that couples can be formed by people with similar market value (assessed as a whole comprehensively). In the same vein, Lee et al (2008) found that men are more influenced than women by the physical attractiveness of their partners and are less affected by how attractive they themselves are, suggesting that men value other traits more when evaluating themselves as romantic partners. Thus, the most preferred traits in a romantic partner of one sex are those that most influence self-perception as a romantic partner in the other (Lee et al., 2008). Women's self-perception tends to be based on the physical attractiveness of other women in the environment (Buss & Shackelford, 2008), while men tend to base their self-perception more on traits indicating social status (Fisher et al., 2008; Goodwin, Marshall, Fülöp, Adonu, & Spiewak, 2012).

In addition to considering that self-perception is based on the market value of other individuals in the environment (Castro et al., 2012; Fisher et al., 2008), in strategic pluralism theory, Gangestad and Simpson (2000) proposed that the strategies adopted by men and women vary according to environmental factors, such as pathogen incidence and resource availability. In this respect, the socioeconomic level of individuals, indicated by their purchasing power, is an environmental factor that could alter self-perception. This effect may be more intense in countries with marked economic inequality, such as Brazil (Gini coefficient of 49.7; Central Intelligence Agency [CIA], 2014), where social inequity is also high. This is important in demonstrating social status and the respect that should be given to individuals with such a status (The Hofstede Centre, 2013). Social status, therefore, indicates both the possibility of individuals owning assets as well as their quality of life and that of their family (Heo, Moser, Chung, & Lennie, 2012). As such, the present study investigated the effect of economic context on the self-perception of men and women as romantic partners within a same environment, namely, a university setting. The economic context was assessed by classifying participants in terms of their purchasing power, and the university was selected due to the similar educational level of the students, whose perspectives on the future should be comparable.

Method

Study Site and Participants

The study was conducted at five institutions of higher learning in the city of Natal, Rio Grande do Norte state, Brazil, with 316 university students aged 18 to 29 years, 109 men (Mage = 22.05; SDage = 2.74 years) and 207 women (Mage = 21.08; SDage = 2.54 years), all heterosexual1. Nearly half of the sample consisted of whites (45.6%), 36.7% mulattos, 8.5% Asian, 5.7% black and 2.5% indigenous (0.9% of participants did not answer the question). These percentages are in line with the population classification of the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE, 2010). Socioeconomic level was distributed as follows: 17.72% class A (family income greater than or equal to 13 minimum monthly wages, > USD 3,900.00), 53.80% class B (family income of around 6 minimum monthly wages, ≈USD 1,800.00) and 28.48% class C (family income of two minimum monthly wages, ≈ USD 600.00). The sample was composed of 37 women and 19 men from class A, 107 women and 63 men from class B and 63 women and 27 men from class C.

Classes D (family income of around one minimum monthly wage, ≈USD 300.00) and E (family income of less than one minimum monthly wage) were removed from the sample due to the small number of participants at these socioeconomic levels.

Instruments

The questionnaire used contained socioeconomic questions (obtained from ABEP-Brazilian Association of Market Research Companies 2010 classification) and others aimed at the self-perception of the participant as a romantic partner.

The ABEP socioeconomic classification is obtained based on a questionnaire to determine the number of assets or services that the participant has at home, Containing the following items: color televisions, DVD players, bathrooms, cars, domestic help, washing machines, freezers, sound systems and refrigerators. The alternatives to quantify each item were zero, one, two, three and four or more. The questionnaire also recorded the head of the household's schooling level, with the following options: no formal education up to the third grade of elementary school, fourth grade of elementary school, complete elementary education, complete secondary education and complete university education. Each answer was awarded a number of points and a final score was recorded for each participant according to socioeconomic level (ABEP, 2010).

With respect to self-perception, participants assessed themselves on nine traits (pretty face, beautiful body, health, sociable, good-humored, sincere, good financial situation, determined/hardworking and intelligent), previously used in other studies (Castro & Lopes, 2011; Castro et al., 2012; Castro, Hattori, Yamamoto, & Lopes, 2014).Subjects could attribute 0 to 9 points for each trait, corresponding to self-assessment of each characteristic. There was also a semantic differential scale along a 10-centimeter line on which participants, by marking a point on the line, evaluate how attractive they consider themselves, varying from not attractive at all (0) to extremely attractive (10).

Procedure

The study was voluntary and respected the anonymity of participants, requiring them to identify themselves only when signing the informed consent form, which contains a brief introduction of the study and the activities performed. It also underscored that the volunteers would not be financially compensated, that they could drop out of the study at any time, and that their identity would be preserved. The form contained the lead researcher's email so that participants could obtain further information, if needed.

The informed consent form was collected separately from the questionnaire and complied with the guidelines and regulatory norms of research involving human beings (Conselho Nacional de Saúde [CNS], 2012). After signing the informed consent form and receiving a copy, participants completed the questionnaire.

Data Analyses

Ten general linear models (General Linear Models - GLM) 2 (sex) x 3 (economic level) were created (one for each characteristic and one for general attractiveness). Thus, we tested whether there is a difference in self-perception as a romantic partner and general attractiveness (dependent variables) according to the economic level and/or sex (independent variables) of the participants. The significance level was set at p < .05. The t-test for independent samples with the Bonferroni correction was used for post-hoc analyses to avoid type I errors (Mittelhammer, Judge, & Miller, 2000).

Results

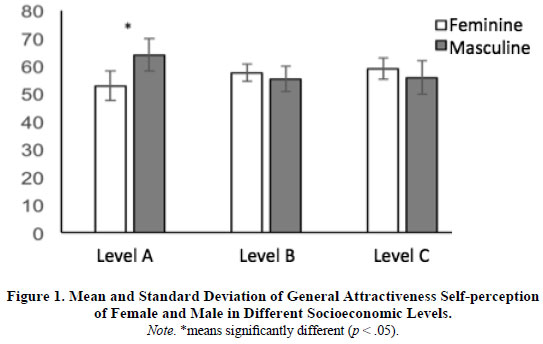

The results obtained showed a significant difference in self-perceived attractiveness between sex and socioeconomic level (Table 1). Independent t-tests were conducted to compare men and women from each socioeconomic level to determine the effect of general attractiveness [t(2.54) = -2.53; p = .015], which indicated that class A men (M = 63.89; SD = 13.03) considered themselves more attractive than class A women (M = 52.89; SD = 16.51). No significant differences were observed for the other comparisons (p > .05).

There was also a difference in economic level for the good financial situation trait (Table 1), in which participants with higher economic levels attributed more points to this trait than their lower socioeconomic level counterparts (Class A: M = 4.89; SD = 1.76. Class B: M = 4.35; SD = 1.53. Class C: M = 3.97; SD = 1.60). For the determined/hardworking trait, the difference was for sex, whereby women deemed themselves more determined and hardworking (M = 6.94; SD = 1.86) than men (M = 6.40; SD = 1.94).

Discussion

With respect to the sexual strategy theory (Buss & Schmitt, 1993), different evolutionary pressures acted on men and women, causing them to modulate their sexual partner preferences, assigning greater value to opposite sex traits that favor an increase in reproductive success. When seeking a romantic partner, primarily for stable relationships, the perceived market value should be similar between the likely couple and, therefore, one of the steps would be self-assessment as a romantic partner (Buston & Emlen, 2003; Castro et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2008).

In general, the traits most desired by the opposite sex are those that are most important for self-perception as a romantic partner (Buston & Emlen, 2003; Castro et al., 2012; Mafra & Lopes, 2014), a factor that influences the selection process. However, it is subject to variations, mainly when sex and the environment are considered, due to the difference in availability and market value of competitors (Gangestad & Simpson, 2000). Thus, in a context with people from different socioeconomic levels, male self-perception tends to change as a function of this variable, given that social status is one of the traits most valued by women seeking a romantic partner (Buss & Shackelford, 2008; Fisher et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2008; Lippa, 2007).

In the present study, although each participant had a particular socioeconomic level, all were from the university environment. Our results corroborate the aforementioned perspective, demonstrating that men from a higher socioeconomic class (A) generally consider themselves more attractive when compared to women's self-perception. Moreover, the results support the strategic pluralism theory (Gangestad & Simpson, 2000), given that men with higher socioeconomic levels consider themselves more attractive than those with lower levels (environmental effect).

There was also a difference between economic level for the good financial situation trait, but this discrepancy is likely attenuated due to the similar perspective for the future of the entire sample, and the difference in self-perception is only noticeable for social status, which directly measures the amount of resources available to the participant and not the other social status traits (intelligence and determined/hardworking) that indicate future social ascension.

Although self-perception was similar between men and women for most of the traits, in agreement with the majority of studies on romantic partners (ex. Buss & Shackelford, 2008; Fisher et al., 2008; Goodwin et al., 2012; Gutierres et al., 1999), the women perceived themselves as being more determined/hardworking than men. Although gender inequality decreased in Brazil in the 1990s, women's unemployment rates remain higher, access to leadership jobs is limited and women in the same jobs as men still earn less, despite high workloads and little social protection (Melo, 2005; Santana, 2010). This result underscores the need for women to work harder than men in order to secure their place in the work force.

The present study revealed that women emphasize the need to be determined and hardworking, while in other investigations men reported these traits as being the most important for self-perception as a romantic partner. This result may be due to the difference in gender equality between the countries under study and Brazil. Human Development Report data (2015) corroborate this hypothesis, revealing the high gender inequality index in Brazil (GII = 0.414) compared to other countries investigated, such as Canada (Fisher et al., 2008) with a GII of 0.098 and Norway (Grøntvedt & Kennair, 2013), with a GII of 0.053.

Furthermore, our findings complement the results of Mafra and Lopes (2014), who found that individuals with different socioeconomic levels, as a function of schooling level, display different self-perception as a romantic partner. However, in the abovementioned study, there was no comparison between socioeconomic classes within a same educational level, which would allow comparison of self-perception among those in the same social setting but with different socioeconomic levels.

Although the nine traits discussed here represent three of the most desired dimensions in the search for romantic partners (pretty face, beautiful body and health as representatives of physical attractiveness; good financial situation, intelligent and determined/hardworking as examples of social status; and sociable, good humored and sincere indicating social skills) (Castro & Lopes, 2011; Castro et al., 2012; Castro et al., 2013; Castro et al., 2014; Mafra, Castro, & Lopes, 2015; Mafra & Lopes, 2014), and overall attractiveness provides information on all the traits assessed together, traits such as active, assertive, caring, desire to have children and independent may also be considered (Kirsner, Figueredo, & Jacobs, 2003), with different weights awarded when a romantic partner is evaluated, demonstrating their importance in assessing self-perception.

Another study limitation is the absence of lower classes (classes D and E) for comparison with all the socioeconomic levels in Brazil. This problem would be solved by broadening and diversifying the sample. However, since we sought to work with participants within a same context, these classes were under-represented, precluding a more far-reaching investigation of socioeconomic levels. The same limitation occurred with respect to non-heterosexuals. Given that romantic partner preferences change according to sexual orientation (see Lippa, 2007 for a review), non-heterosexual participants were excluded from the sample.

Moreover, the research presented here was conducted in only one Brazilian city, which ruled out determining self-perception differences in relation to socioeconomic status at the national level. As such, we suggest a more comprehensive study be carried out, collecting data from all the regions in the country. We also recommend that future studies investigate whether there is a difference in self-perception as a romantic partner between non-heterosexuals from different socioeconomic classes.

Conclusion

Although the results demonstrated that both men and women are sensitive to their financial situation, the effect was more pronounced in men, confirming that socioeconomic level is a factor that influences male self-perception, likely because women tend to adopt more long-term strategies and value more the traits in a potential partner that indicate investment in offspring. On the other hand, our sample behaved differently from other populations, showing that women considered themselves more determined/hardworking than men, requiring the former to work more than the latter to guarantee their place in the work force.

References

Buss, D. M. (1989). Sex differences in human mate preferences: Evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures. Behavioral and Brain Science, 12,1-49. [ Links ]

Buss, D. M., & Schmitt, D. P. (1993). Sexual strategies theory: An evolutionary perspective on human mating. Psychological Review, 100,204-232. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.100.2.204 [ Links ]

Buss, D. M., & Shackelford, T. K. (2008). Attractive women want it all: Good genes, economic investment, parenting proclivities, and emotional commitment. Evolutionary Psychology, 6(1),134-146. [ Links ]

Buston, P., & Emlen, S. (2003). Cognitive processes underlying human mate choice: The relationship between self-perception and mate preference in Western society. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(15),8805-8810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1533220100 [ Links ]

Castro, F. N., & Lopes, F. A. (2011). Romantic preference in Brazilian undergraduate students: From the short term to the long term. Journal of Sex Research, 47,1-7. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2010.506680 [ Links ]

Castro, F. N., Hattori, W. T., & Lopes, F. A. (2012). Relationship maintenance or preference satisfaction? Male and female strategies in romantic partner choice. Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology, 6(2),217-226. [ Links ]

Castro, F. N., Hattori, W. T., Yamamoto, M. E., & Lopes, F. A. (2013). Romantic partners in a market perspective: Expectations about what ensures a highly desirable partner. Psychological Reports: Relationships & Communications, 113(2),605-618. doi: 10.2466/21.19.PR0.113x23z6 [ Links ]

Castro, F. N., Hattori, W. T., Yamamoto, M. E., & Lopes, F. A. (2014). Social comparisons on self-perception and mate preferences: The self and the others. Psychology, 5,688-699. doi: 10.4236/psych.2014.57080 [ Links ]

Central Intelligence Agency. (2014). The World Factbook. Retrieved from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/br.html [ Links ]

Conselho Nacional de Saúde. (2012). Resolução nº 466, de 12 de dezembro de 2012. Dispõe sobre diretrizes e normas regulamentadoras de pesquisas envolvendo seres humanos. Recuperado em http://conselho.saude.gov.br/resolucoes/2012/Reso466.pdf [ Links ]

Dosmukhambetova, D., & Manstead, A. (2011). Strategic reactions to unfaithfulness: Female self-presentation in the context of mate attraction is linked to uncertainty of paternity. Evolution and Human Behavior, 32,106-117. doi: 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2010.08.006 [ Links ]

Fisher, M., Cox, A., Bennett, S., & Gavric, D. (2008). Components of self-perceived mate value [Special Issue: Proceedings of the 2nd Annual Meeting of the North-Eastern Evolutionary Psychology Society]. Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology, 2(4),156-168. [ Links ]

Gangestad, S. W., & Simpson, J. A. (2000). The evolution of human mating: Trade-offs and strategic pluralism. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 23,573-644. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X0000337X [ Links ]

Gaulin, S. J., & McBurney, H. D. (2001). Psychology: An evolution approach. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Geary, D., Vigil, J., & Byrd-Craven, J. (2004). Evolution of human mate choice. Journal of Sex Research, 41,27-42. doi: 10.1080/00224490409552211 [ Links ]

Goodwin, R., Marshall, T., Fülöp, M., Adonu, J., & Spiewak, S. (2012). Mate value and self-esteem: Evidence from eight cultural groups. PLoS ONE, 7(4),e36106. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036106 [ Links ]

Grøntvedt, T. V., & Kennair, L. E. O. (2013). Age preferences in a gender egalitarian society. Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology, 7(3),239-249. [ Links ]

Gutierres, S., Kenrick, D., & Partch, J. (1999). Beauty, dominance, and the mating game: Contrast effects in self-assessment reflect gender differences in mate selection. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25(9),1126-1134. doi: 10.1177/01461672992512006 [ Links ]

Hattori, W. T., Castro, F. N., & Lopes, F. A. (2013). Mate choice in adolescence: Idealizing romantic partners. Psico, 44,226-234. [ Links ]

Heo, S. Moser, D. K., Chung, M. L., & Lennie, T. A. (2012). Social status, health-related quality of life, and event-free survival in patients with heart failure. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 11(2),141-149. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2010.10.003 [ Links ]

Human Development Report. (2015). Gender Inequality Index (GII). Retrieved from http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/gender-inequality-index-gii [ Links ]

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. (2010). Síntese de indicadores sociais: Uma análise das condições de vida da população brasileira. Estudos & Pesquisas: Informação Demográfica e Socioeconômica, 27. [ Links ]

Kenrick, D. T., Sadalla, E. K., Groth, G., & Trost, M. R. (1990). Evolution, traits, and the stages of human courtship: Qualifying the parental investment model. Journal of Personality, 58(1),97-116. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1990.tb00909.x [ Links ]

Kirsner, B. R., Figueredo, A. J., & Jacobs, W. J. (2003). Self, friends, and lovers: Structural relations among Beck Depression Inventory scores and perceived mate values. Journal of Affective Disorders, 75,131-148. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00048-4 [ Links ]

Kruger, D., Fitzgerald, C., & Peterson, T. (2010). Female scarcity reduces women's marital ages and increases variance in men's marital ages. Evolutionary Psychology, 8(3),420-431. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/147470491000800309 [ Links ]

Lee, L., Loewenstein, G., Ariely, D., Hong, J., & Young, J. (2008). If I'm not hot, are you hot or not? - Physical attractiveness evaluations and dating preferences as a function of one's own attractiveness. Psychological Science, 19(7),669-677. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02141.x [ Links ]

Lippa, R. A. (2007). The preferred traits of mates in a cross-national study of heterosexual and homosexual men and women: An examination of biological and cultural influences. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 36,193-208. doi:10.1007/s10508-006-9151-2 [ Links ]

Mafra, A. L., Castro, F. N., & Lopes, F. A. (2015). Investment in beauty, exercise, and self-esteem: Are they related to self-perception as a romantic partner? Evolutionary Psychological Science, 2(1),24-31. doi: 10.1007/s40806-015-0032-6 [ Links ]

Mafra, A. L., & Lopes, F. A. (2014). "Am I good enough for you?" Features related to self-perception and self-esteem of Brazilians from different socioeconomic status. Psychology, 5(7),653-663. doi: 10.4236/psych.2014.57077 [ Links ]

Melo, H. P. (2005). Gênero e pobreza no Brasil (Relatório Final do Projeto Governabilidad Democratica de Género en America Latina y el Caribe). Brasília, DF: Comissão Econômica para a América Latina e o Caribe. [ Links ]

Mittelhammer, R. C., Judge, G. G., & Miller, D. J. (2000). Econometric Foundations. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Pawlowski, B. (2000). The biological meaning of preferences on the human mate market. Anthropological Review, 63,39-72. [ Links ]

Santana, A. M. (2010). Mulher mantenedora/homem chefe de família: Uma questão de gênero e poder. Forum Identities Magazine, 4,71-87. [ Links ]

The Hofstede Centre. (2013). National Culture. Retrieved from http://geert-hofstede.com/brazil.html [ Links ]

Trivers, R. (1972). Parental investment and sexual selection. In B. Campbell (Ed.), Sexual selection and the descent of man (pp. 136-179). Chicago, IL: Aldine-Atherton. [ Links ]

Received: 22/03/2017 1 Only heterosexuals were used due to the insufficient number of non-heterosexuals to form a separate group. Mailing address:

Mailing address:

Anthonieta Looman Mafra

Universidade Potiguar, Pro-Reitoria Academica, Mestrado Profissional em Psicologia Organizacional e do Trabalho

Capim Macio

Natal, RN, Brazil 59082-902

Phone: (84) 3215 1234

E-mail: looman.anthonieta@gmail.com, castrofn@gmail.com and fivialopes@gmail.com

1st revision: 29/11/2017

Accepted: 18/02/2018

Support: Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq).

texto em

texto em